The Horologist’s Loupe

The Horological Society of New York's newsletter (and today blog!) began publishing in 1936, and is one of the oldest continuously running horological publications in the world.

Reading Time at HSNY: Form Time to Time

This post is part of a series, Reading Time at HSNY, written by our librarians. Today’s post was written by Miranda Marraccini.

Picture this: you roll up to a meeting at work a few minutes early. Eyeing the empty seats around the perimeter of the conference table, you put your hand in your pocket and pull out…a tiny pair of deep red cherries. Is it some bizarre snacking ritual, your team wonders? A display of power over your dilatory direct reports? Suddenly, you pop open one of the cherries with a flourish, revealing a watch dial where the pit should be. You were checking the time! Everyone in the conference room is impressed and astonished.

Image 1

Thank you for indulging me in this scene. It’s imaginary, but the watch I described is very real, made in Geneva around 1830. Each cherry is about 20 mm across; the non-watch cherry contains perfume (image 1). These kinds of fantastical watches in unusual shapes are often called “form watches”; I contributed to an article in The New York Times about them in 2023.

At the end of the 18th century and the beginning of the 19th century, improvements in the technology of enameling and engraving on metal encouraged creativity in watch production. Artisans conjured realistic but tiny fruits, animals, hot air balloons, and different miniaturized musical instruments including lyres, mandolins, and even bagpipes. They are meant to be beautiful first, but they also show off the technical mastery of the Genevan artisans who created them–it is very difficult to create such tiny watch movements–ones as small as 10 mm across.

In “Watches of Fantasy,” a book in our library at the Horological Society of New York (HSNY), Fabienne Sturm has some ideas about why form watches were created, including to soften the inevitable blow of time passing. Time “endears himself to us when we measure his passing in the heel of a wooden shoe or under the wings of a pair of doves,” Sturm writes (I’ve included an image of the shoe she references in the header above.)

Image 2

I think this idea of watches reminding us of the bittersweet reality of time is especially true of watches that depict creatures that we think of as ephemeral, like butterflies or ladybugs. These watches demonstrate that time is passing on their dials, but also rebel against the effects of time by using materials that will last for centuries: imagine a fresh apple that never rots, a tulip always blooming. In image 2, an ornately enameled polychrome pear opens up to reveal not only a watch, but also a “perfume flask, portrait holder, mirror, and beauty-spot box.” You might notice perfume coming up a few times in this article–the way that scent evokes memory and desire seems to have a historical connection with horology. (That’s why we bottled our own HSNY fragrance!)

In Europe, form watches or fantasy watches reached the peak of their popularity at the beginning of the 19th century. This was before the wristwatch was invented. Both men and women were wearing their watches on chains, and as a result, the watches were often concealed in their pockets. According to Genevieve Cummins in “How the Watch Was Worn,” women first started to wear their watches on display on ornamental chatelaines, which also attached other useful objects like scissors and keys. Then they began to wear the watches alone as pendants around their necks.

Image 3

One from about 1830 is a watch in the form of a large key, which is also a pencil holder (image 3). Often, the watch dial is concealed beneath an enamel or metal cover. Some of the watches move: a flower bud that opens to reveal a dial inside, or a butterfly that spreads its wings. Some of them even contain musical automata.

Image 4

I particularly enjoy a little pistol from the early 1800s (image 4). It’s elaborately enameled and be-pearled, with a hidden compartment in the handle that conceals a tiny watch dial. If you pull the trigger, pop! Suddenly, a flower bud blooms from the end of the pistol, which in turn squirts perfume from its center. I think I personally like this one because of the way it takes an object associated with violence and makes it incredibly delicate and gem-like.

Image 5

Image 6

Image 7

I also like watches shaped like snails because they take advantage of the snail’s natural curved shell, and I think there’s a funny play on the idea of a snail moving slowly while time rushes ahead (image 5). Probably the most surprising animal I’ve seen represented as a watch is a sheep (image 6). Turn the sheep over and the reverse shows a lion (well, an approximation of a lion, if you squint). It’s a watch, it’s a parable, it’s a warning.

Some of the watches are “curio watches”—not meant to be worn or even really carried, they perform a second and even third function besides telling time. These include watches built into beauty-spot cases, vinaigrettes, glasses cases, snuff boxes, salt shakers, bouquet holders, and notebooks. From the 19th century onward, watches were built into cufflinks, cane handles (image 7), cigarette lighters, purses, compacts for makeup, card cases, and even mechanical pencils (as in one made by Tiffany & Co., in image 8).

Image 8

Image 9, from the book “A Dictionary of Wonders: Van Cleef & Arpels,” shows a 1934 example of an accessory called a minaudière. This little case, usually made of guillochéd metal and sometimes ornamented with jewels, could fulfill all the necessary public functions for a liberated woman of the 1920s: a detachable clip that could be reconfigured into a brooch, a makeup case, a mirror, a cigarette holder, a lighter, and of course, a watch. In image 9, the watch dial pops out from behind a rectangular hinged cover on the right side of the case.

Image 9

Image 10

In the 1960s, there was a fashion for pendant watches again. One that seems to come up a lot is a ladybug or beetle, often marketed to kids (You can see an example in the 1966 Oris ad reproduced in “How the Watch was Worn,” image 10). The wings open to reveal the watch underneath. My mom remembers wearing (and treasuring!) her ladybug watch in the 1960s. They’re still made today and vintage examples are being sold on places like Etsy. You can ogle some charming 20th-century examples of pendant watches and ring watches on the Little Old Watches Instagram account, run by Kaitlin Koch.

Image 11

As wristwatches became more popular in the 20th century, fewer people were wearing pendant watches and pocket watches. It’s not as feasible to wear a wristwatch in the form of a strawberry or a tiny shoe, so form watches or fantasy watches became rarer. But one could argue that the tradition of novelty watches is carried on in character watches, shaped like Garfield, Kermit, or C-3PO (image 11, from “Comic Character Wristwatches”).

Very recently, modern watchmakers have taken up the idea of watches shaped like animals, for example, a spider or a T. rex. One company heavily invested in these whimsical watches is Maximilian Büsser & Friends (known as MB&F). Image 12, from “MB&F the First Fifteen Years,” shows the “JwlryMachine,” a watch collaboration between MB&F and Boucheron in the shape of an owl. Under a translucent feathery breast carved out of rose quartz, the winding rotor swings, “to mimic the beating of the owl’s heart.”

Image 12

Some of these watches verge on automata, which could be a whole other article. And some automata run on watchwork, but no longer incorporate a dial that tells the time: a tortoise (another famously slow mover), and a snail with a hare’s head (moving both slowly and quickly).

What if your watch, instead of a simple circle or cushion case, could be a tiny pizza slice or miniature rocket ship? What would you want your fantasy form watch to look like? The watches in this article are proof that form doesn’t need to follow function; form is an independent entity, a wild creature without limits, following nothing.

The Horological Society of New York Announces 2026 Global Financial Aid Opportunities for Watchmaking Students

New Independent Watchmaker Grant Joins Expanded Scholarship Portfolio

The Horological Society of New York (HSNY) announces its 2026 financial aid opportunities for watchmaking students and professionals. With HSNY’s scholarship budget tripling in 2026, thanks to the generous support of the Vogt Foundation, this is the first year applications will be open globally, expanding access to financial aid for watchmaking students worldwide. The comprehensive portfolio includes 10 scholarships and awards, highlighted by the newly established Independent Watchmaker Grant, which supports practicing independent watchmakers in advancing their craft and businesses.

About the New Independent Watchmaker Grant

The HSNY Independent Watchmaker Grant supports emerging independent watchmakers by providing funding for essential tools and startup expenses. This program is designed to encourage innovation and craftsmanship at the highest level of horology. Grant recipients are selected based on criteria that include originality of concept, quality of finishing, and excellence in design, with special emphasis placed on projects that explore complications and novel mechanical movements. Through this initiative, HSNY advances its mission to support technical skill, artistic expression, and independent creativity within the watchmaking community.

Independent watchmakers who are developing original timepieces are eligible to apply for the HSNY Independent Watchmaker Grant. Awards of up to $50,000 are available.

2026 Financial Aid Opportunities

In addition to the new Independent Watchmaker Grant, HSNY is offering nine scholarships to support watchmaking students and institutions globally. Veterans, students, and practicing watchmakers interested in applying can find detailed information on HSNY's website at www.hs-ny.org.

Last year, HSNY awarded a record $160,000 in scholarship funds to 28 students and four watchmaking schools.

The application period is from January 1 to March 1, and financial aid is awarded in March.

Independent Watchmaker Grant (New for 2026)

The Andre Bibeau Scholarship for Veteran Watchmaking Students

The Benjamin Banneker Scholarship for Black Watchmaking Students

The Oscar Waldan Scholarship for Jewish Watchmaking Students

To download the official press release, click HERE.

For media requests, please email Nick Roberts at nick@lawrencepr.co or Carolina Navarro at carolina@hs-ny.org.

About the Horological Society of New York

Founded in 1866, the Horological Society of New York (HSNY) is one of the oldest continuously operating horological associations in the world. Today, HSNY is a 501(c)(3) nonprofit organization dedicated to advancing the art and science of horology through education. Members are a diverse mix of watchmakers, clockmakers, executives, journalists, auctioneers, historians, salespeople, and collectors, reflecting the rich nature of horology in New York City and around the world. http://hs-ny.org.

Reading Time at HSNY: Staging Time for the Masses

This post is part of a series, Reading Time at HSNY, written by our librarians. Today’s post was written by our Fall 2025 intern, Natalie Zak.

This past fall, I had the pleasure of serving as the Library Intern at the Horological Society of New York (HSNY), helping process a portion of the archival materials held in the Society’s backroom on 44th Street in Midtown Manhattan. I was given free reign at the start to choose what kind of subcollection I’d like to build, based on my interests. As a recent Master of Library and Information Science (MLIS) graduate, this was a daunting task.

We are taught that as archivists, we must abide by the original order where and when we can, arranging and processing collections as they are received, rather than creating categories where there weren’t any before. However, this principle, more formally referred to as respect des fonds, does not apply to most of the archival materials currently held at HSNY.

There is no original order to these materials; they arrived in an array of boxes, each filled to the brim with a miscellany of horological ephemera from the comprehensive collection of Fortunat Mueller-Maerki. My project, and future interns’ projects, aim to categorize it, creating as we go artificial subcollections, so that library patrons may one day be able to access and make use of these incredibly diverse materials for personal and professional research. So, in September, I began making my way through the piles, setting aside brightly colored pamphlets, spiral-bound booklets, and catalogs that caught my eye. What I found, upon assessing my own personal pile, was that I had been gravitating towards library, museum, and institutional ephemera that documented conversations happening within the field. This included everything from library catalogs to subject bibliographies to museum brochures, with symposia and convention materials mixed in as well.

Initially, the relationship between these items appeared tenuous. Does a bibliography of Swiss scholar Alfred Chapuis’ writings belong in the same collection as, say, a museum catalog from Nezu Museum in Japan? The answer: Yes, yes it does. Both Chapuis’ writings and the museum exhibition contributed to public consciousness and interest in horology.

A discipline (like horology) is sustained by conversation, collaboration, and interest. And in order to create interest, horologists and collectors must bring members of the public into the conversation. In my opinion, this relationship is best exemplified by the HSNY’s collection of museum and exhibition catalogs because they exist on the boundary of public and private. By taking a closer look, we see ways in which institutions and members of the discipline have contextualized their craft to appeal to new audiences. They move beyond simply asking people to behold a beautiful clock. Rather, they ask people to behold the subject of time itself.

Time appears repeatedly throughout these materials as something learned, staged, feared, explained, and even moralized. The exhibitions in this collection move beyond simple presentation of clocks and watches, instead exploring the astronomical and mechanical origins of timekeeping; the historical and cultural conditions that shape our understanding; and the spectacular, confounding devices that are born from a deep appreciation for time.

Time as a Way of Knowing the Universe

One theme that arose as I made my way through the catalogs is the presentation of time as a way of knowing the universe. Across the museum catalogs and brochures, time is repeatedly defined not as an abstract unit, but as a way of reading the universe — derived from planetary motion, calibrated against the sun, and materialized in instruments that translate celestial order into human understanding.

Image 1

Image 2

A catalog for the 1974 “Période archaïque et antiquités” exhibition at Musée international d’horlogerie in La Chaux-de-Fonds, Switzerland, is a clear example of this conception of time. It begins not with clocks, but rather with a planetarium (images 1-2). Framing time as a cosmological problem, the exhibition presents early timekeeping as born from, roughly translated, “the need to align human life with solar and lunar cycle.”

Image 3

The language the catalog uses is urgent and impactful too, drawing in potential audiences by connecting their experience of time with a higher purpose: “The movement of the heavens imposed order on human life.” Time is presented as something derived from observation of cosmic regularities, not human convention or intervention. This is something greater than us, heavenly even. We simply must do the only thing we can: “Go and observe.”

From La Chaux-de-Fonds, this way of presenting time travels outward. In brochures for the Eise Eisinga Planetarium in the Netherlands, the planetarium itself is the horological instrument: a space designed to teach time through the visible order of the heavens (image 3). But it’s more than just the planetarium; it’s the story of why it was made that matters.

In 1774, the Frisian wool-comber Eise Eisinga began building the planetarium that now bears his name in his own home in Franeker to prevent astronomical panic. A local preacher, Eelco Alta, circulated a pamphlet predicting that an upcoming conjunction of the moon, Mercury, Venus, Mars, and Jupiter would pull the Earth out of its orbit and bring about catastrophe. Alarm spread quickly among the public.

Eisinga, trained in mathematics and astronomy, set out to counter that fear by constructing a working model of the solar system. He built a fully mechanical planetarium in a private living room, driven by a pendulum clock, modeling real planetary motion. Through it, he demonstrated the regular, predictable motion of the planets and showed that no such disaster would occur (images 4-5). Timekeeping here is more than just measuring motion by observing the planets. It’s a tool for cosmological explanation, public reassurance, and a way of regulating a model of the universe itself.

Image 4

Image 5

Thus, as is written in the brochure for Kulturmuseum St.Gallen’s 2024 exhibition on mathematician and horologist Jost Bürgi, titled “Jost Bürgi (1552–1632) – Schlüssel zum Kosmos”: “Through meticulous celestial observations and precise calculations, a dramatic shift in the worldview of European cultural history began to take shape” (images 6-7). The “dramatic shift” is not philosophical alone, but mechanical, rooted in Europeans’ increasing ability to measure time with enough precision to support empirical astronomy.

Image 6

Image 7

Image 8

If the planetarium presents time as a way of explaining the cosmos to the public, the brochures for the Jost Bürgi exhibition and the Museum of Dutch Clock’s “Seven centuries of time-keeping in the Netherlands” exhibit, from 2008, move that cosmological framework directly into the mechanics of timekeeping itself. In the Kulturmuseum St. Gallen brochure on Bürgi, precision is framed not as an end in itself, but as a prerequisite for knowing the heavens. Bürgi’s work is positioned within a moment when increasingly exact time measurement became essential to astronomical observation, navigation, and calculation, collapsing the distance between celestial theory and mechanical practice.

The Museum of Dutch Clocks exhibition takes this one step further, embedding astronomical knowledge into objects meant for everyday use (images 8-9). Longcase clocks, planisphere clocks, and other domestic timepieces display the position of the sun in the zodiac, the length of day and night, and even world time, folding planetary motion into the rhythms of daily life. Here, the universe is no longer something merely observed or demonstrated. It is engineered, housed, and kept running on the wall or in the corner of a room, making cosmological order a constant presence within ordinary timekeeping.

Image 9

Time as Performance, Illusion, and Delight

If implicating the public in a higher, unknowable (yet, as we discussed, ultimately knowable) power isn’t enough to pique their interest in the discipline, then we turn to the spectacular. Flashiness sells, and as you will see, some exhibitions lean into movement, sound, and illusion, presenting time not as something to be calculated, but rather as something to be seen, heard, and felt. As accuracy recedes into the background, what comes forward instead is delight.

Catalogs for automaton exhibits encapsulate this perfectly. La magie des automates au XIXᵉ siècle, a temporary exposition hosted by a bank in Brussels (29 April–18 May 1993) featured automata from private collections, not objects meant for measurement, but machines that imitate life. As the catalog notes, the term automaton became specialized “to designate machines that imitate the movements of living beings” in the 18th century.

The catalog descriptions linger not on gears or escapements, but instead on coordinated gestures and sequences of motion: singing birds that turn their heads and open their beaks (image 10); a snake charmer whose arms, head, and serpent move together in a controlled rhythm (image 11). Time here is neither abstract nor numerical; it’s experienced as sequence, pacing, and repetition. These machines don’t measure time — they perform it.

Image 10

Image 11

A similar logic governs an animated floral clock in a catalog for Nezu Museum (image 12). The catalog describes flowers arranged in a radiating form that rotate continuously, while twelve small petals below open and close in succession. The rotation of decorative elements, we are told, “creates a visual rhythm that marks the flow of time,” giving the impression that the entire structure is alive with movement. Here, time is aestheticized. Motion itself becomes the sign of temporal passage, and ornament carries as much meaning as mechanism. The clock functions as a moving artwork, where animation replaces precision as the primary mode of engagement.

Image 12

Sound introduces yet another dimension of performed time in materials in HSNY’s collection, covering the Britannic Organ, which was originally intended for installation on the sister ship to the Titanic but ended up in the collection of the Museum für Musikautomaten in Seewen, Switzerland (images 13-14). Although capable of remarkable technical precision, the organ is framed primarily through its ability to activate sound in real time. Music is triggered and regulated by clockwork mechanisms, reproducing performances through rolls that unfold in carefully controlled sequences.

Image 13

Image 14

The most overtly spectacular examples appear in “Artistry in Time: Decorative Timepieces of Imperial China,” an exhibition at EPCOT, Walt Disney World, in 1987-1988 (image 15). These clocks, originally from The Palace Museum in Beijing, were designed explicitly to entertain. Musical signals mark the hour and quarter-hour, setting elaborate sequences into motion: pagodas rise, figures rotate, fountains flow, animals move (image 16).

These are items that were “designed not only to tell time but to delight the court through elaborate automata, musical elements, and richly symbolic decoration.” Despite timekeeping being considered widely to be a necessary act, symbolism, display, and grandiosity have always mattered when it comes to capturing the public’s hearts and minds.

Image 15

Image 16

Ultimately, what emerges from this material is not a story about objects alone, but about mediation. These catalogs document moments when horology steps outside of itself and asks how time might be made compelling or even pleasurable to those without technical training. The answers vary. Sometimes time is elevated, aligned with the heavens and cosmic order. Sometimes it is disciplined. Other times, it is animated, musical, and theatrical. But in each case, the goal is the same: to make time legible by staging it.

Seen together, these exhibitions reveal a discipline that has long understood the limits of technical authority. Horology does not sustain itself through accuracy alone. It sustains itself through performance. Planetariums, automata, musical instruments, and decorative clocks are not peripheral to this history. They are evidence of how timekeeping has been repeatedly embedded in narrative and shared experience so that it may continue to be culturally meaningful.

Reading Time at HSNY: Serving Up Seconds

This post is part of a series, Reading Time at HSNY, written by our librarians. Today’s post was written by Miranda Marraccini.

I ended my last article with photographs of some truly spectacular bread roosters from a book in our library collection at the Horological Society of New York (HSNY). (What does a rooster-shaped loaf have to do with horology? You’ll have to read it to find out!) Well, after that savory hors d'oeuvre, it turns out the horological masses were positively CLAMORING for more epicurean content. And I’m always happy to focus on food, in my writing as in my life. I’ve whipped up some mouth-watering tidbits for you today: watches that look good enough to eat (but you must resist!), chefs who flash wrist-candy in the kitchen, clock-themed eateries, and in-jokes involving edible hairsprings.

Image 1

Image 2

Let’s start with breakfast: a cup of tea, perchance? The eccentric horological contraption in image 1 is called a teasmade, a delicious portmanteau if I ever heard one. It’s the cover illustration for the straightforwardly titled “Eccentric Contraptions,” a book in our library. According to the author, the Victorians invented this device to make a brew without emerging from your warm duvet: “when the alarm clock triggered the switch, a match was struck, lighting a spirit stove under the kettle. When the water came to the boil, the steam pressure lifted a hinged flap, allowing the kettle to tilt and fill the teapot; then a plate swung over the stove and extinguished the flames.” Seems foolproof to me! This particular teasmade comes from Birmingham, the center of the watch and jewelry trade in England at the turn of the 20th century.

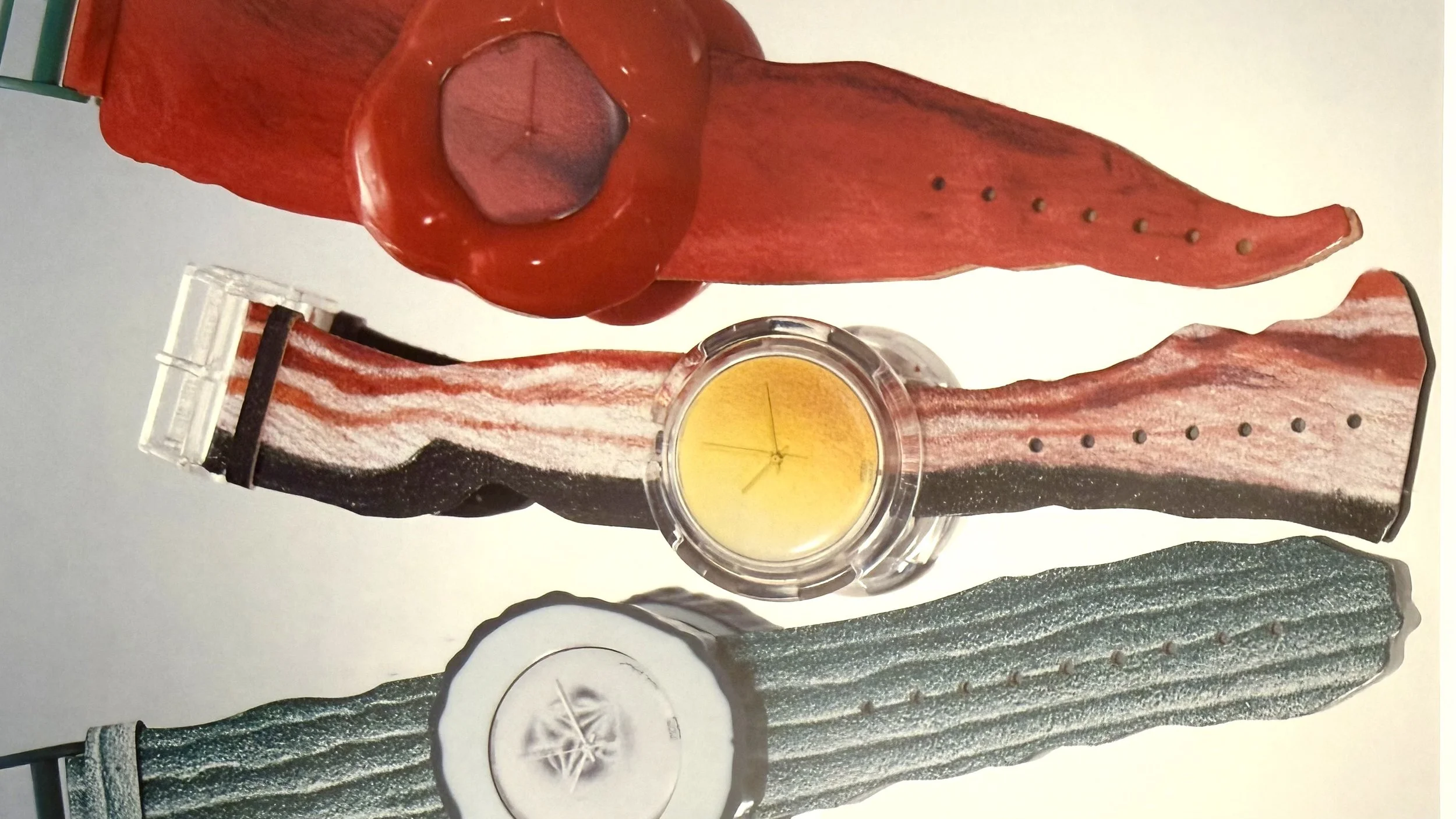

Now that we’ve had tea, would you fancy some eggs and bacon, with a side of fresh-cut, glistening veggies? The wacky non-edible Swatch watches in image 2, designed by Alfred Hofkunst, premiered in 1991 as a limited edition. As a promotion, Swatch sold them in actual vegetable markets. There’s a cucumber, a fried egg over a strip of bacon, and a red pepper model, all rendered in delectably detailed plastic and rubber. A page from the book “Swatchissimo, 1981-1991,” which celebrates the first 10 years of Swatch production, shows these watches in all their puffy glory. My favorite feature is the names of the models, which are multilingual puns: “gurke” means “cucumber,” so “Gu(h)rke” incorporates an h in the word to form a pun on the German “uhr,” meaning clock or watch. The breakfast one is called “Bonju(h)r,” a similar French/German pun, while the pepper watch “Verdu(h)ra,” plays on the Italian and Spanish word for “vegetable.”

As you might imagine, these food Swatches are collectible, with a set on eBay available for $630 at the time of writing. Have you always wanted to embody the crispness of a crudité tray? Or would you feel perturbed by a brunch guest missing their fork and biting your wrist instead? That’s certainly a risk you’ll have to take if you want to wear one of these.

If watches can be food, then watches can appeal to those in the food industry. Celebrity chefs are a known watch-collecting community, with chef-watch couplings reading like wine pairings on a menu: Kristen Kish and her Cellini, Dominique Crenn and her Royal Oak, Gordon Ramsay and his white gold Submariner “Smurf” (or one of his many others). Hodinkee recently ran an article by multi-hyphenate chef and writer Eddie Huang in which Huang nominally discusses wearing a watch in the kitchen, while musing about Pop Smoke, getting T-boned in a car full of loose marijuana, and the excruciating mundanity of the hamburger.

In “A Man & His Watch,” a popular book in our library, a couple of chefs are featured, including Eric Ripert, the chef and co-owner of Le Bernardin in New York. In the book, a collection of first-person testimonials, Ripert compares the craftsmanship of cooking to that of watchmaking, writing: “Take making a sauce: you can’t measure an ounce of flavor–it doesn’t exist that way. It’s intangible; you can’t dissect it…So it’s the same with watches: it’s craftsmanship until you reach a certain level of complexity. Then it’s artistry.” Ripert also admits to “banging up” expensive watches in the kitchen: “I have the watch to use the watch!” He wears a Vacheron Constantin Historiques American 1921.

Image 3

Most modern watches are sturdy enough to withstand the steamy, high-contact world of a restaurant kitchen, but this robustness is a relatively recent development. In image 3, an ad that appeared in American Horologist and Jeweler in 1965 touts the development of Incabloc technology. Incabloc is a patented shock protection system invented in 1934; it uses a special spring mounted over a jewel to shield the delicate balance staff from impact when a watch is dropped. According to this Europa Star article, which covers this handy invention in more detail, more than 80% of all watches utilized Incabloc by the 1960s.

In image 3, an ad for Incabloc demonstrates its shock protection feature by comparing a watch to a fragile egg. On the right is a broken shell; on the left is an intact egg, with a cutout showing an undamaged watch movement, with its Incabloc system visibly in place. It stands out because the red ruby is the only part of the ad in color, except for the lyre-shaped spring that is the company logo at the bottom.

We’ve covered celebrity chefs and their watches, but haute cuisine doesn’t have a monopoly on horology. A decidedly less upscale establishment that features in our collection is the Tick Tock Tea Room, pictured in an undated postcard in image 4. This picture stands out immediately among our horological postcards, which mostly feature public clocks, museums, vintage watch advertisements, or historic factories. This card, in contrast, shows a cozy, if dated, red and pink dining room furnished with crimson diner chairs so pleathery-looking you can almost hear them squeak, and decorated with an entire estate sale’s worth of clocks.

Image 4

The Tick Tock was a Hollywood, CA standby that opened in 1930 and lasted until 1988. It served cheap, filling comfort food to lonely transplants, according to this local history, making a name for itself with 65-cent turkey dinners and orange sticky rolls. Art and Helen Johnson, who moved west from Minnesota, decorated the cafe’s first location with a single cuckoo clock, and the theme kind of exploded from there. I can spot at least nine clocks in the grainy photograph above; available photos online show even more.

I think the clocks make the space feel cozy, though I do wonder if the ticking was intolerable. Maybe the Johnsons didn’t keep all the clocks running. From the nostalgic descriptions I read, it seems like the decor helped Angelenos feel like they had a kind of home, where someone was there day or night to welcome them to a dinner table groaning with mountains of potatoes. Perhaps I’m romanticising, but this is the LA I imagine from movies, the way LA imagines itself.

Image 5

For the New Yorkers out there, there’s nothing more local than a bagel. I like an everything bagel with scallion cream cheese myself, but perhaps you prefer nova, capers, or even a BEC? (If it’s a cinnamon raisin bagel that thrills you, we might not be friends.)

We found the drawing in Image 5 in our administrative archives at HSNY. Titled “How to prepare & consume a New York gourmet’s delight,” it depicts a bagel with lox and schmear, separated into its component layers, schematic-style. They are neatly numbered and captioned from top to bottom, with each striation representing a horological in-joke. The top half of the bagel (1A) represents HSNY, while the lox represents the Bulova and Seiko watch companies. At the bottom of the image, an arrow points from the “assembled melange” into the gaping mouth of a bespectacled eater, presumably the gourmet of the title.

We think this was the creation of an HSNY member in the 1970s. There are layers to this sandwich that I will never understand. Why, for instance, are all the parts of the sandwich representative of HSNY except for the lox? Does the inclusion of the Bermuda onion indicate a reference to a specific member (maybe someone who retired to Bermuda?) And most pressing, what kind of bagel is HSNY???

Although the bagel in image 5 is merely symbolic, HSNY hosted “a series of entertainments, picnics and dances” featuring actual food starting with our beginnings as the Deutscher Uhrmacher Verein (German Watchmakers’ Society). The earliest of these events were humble “smokers,” but they evolved into elaborate banquets and eventually into the black-tie galas we host today at venues like the Plaza Hotel. (A few tickets still available for 2026!) In image 6, a selection of banquet programs gives a sense of the scope of celebration over the years.

Image 6

Image 7

In this 2023 article I wrote about HSNY galas and banquets, you can get a real mouthful of what HSNY members and their guests were eating over the years. If I were eating at an elegant HSNY gala in the 20th century, I’d go for the amontillado sherry, the “grapefruit supreme,” or the “tutti frutti ice cream logue,” but skip the “sweetbreads en casserolettes.” To each their own, however!

An early German-language banquet menu in our archives, from 1912, includes some standards like oysters and Brussels sprouts, but also some curious items like “enamel filet with cuvette sauce,” “horological cream puffs,” “spindle clock cheese,” and under salads, “etched hairsprings with double-proofed acidic chronometer oil.” All of the delicious dishes involve puns on watch and clock parts.

If all of this inspires you to get into the kitchen yourself, why not take inspiration from one of our new library acquisitions, “The Gilded Age Christmas Cookbook.” We acquired the volume for our library because of HSNY’s own 19th-century past, recently featured in HBO’s “The Gilded Age,” seasons two and three. Written by Becky Libourel Diamond, the book includes adaptations of real Gilded Age recipes for the festive season (including Hanukkah and New Year's) interspersed with short essays about celebratory practices of the period. Image 7 shows a recipe for “mock mince pie,” a dessert to round out our meal today.

I just ate my weight in potatoes, so I’m too full to be tempted by all the horological treats I’ve written about here. However, I do hope this will inspire you as we head into the holiday season, when every time of day is an acceptable snacking time, and when each hour marker on the dial, if you look closely, just reads “yum.”

HSNY Expands Financial Aid Programs With Donation From the Vogt Foundation

To Support Watchmaking Education & Innovation

The Horological Society of New York (HSNY) is proud to announce a transformative $470,000 donation from the Vogt Foundation, funding two key initiatives that will advance watchmaking education and support the next generation of horological talent.

Scholarship Program Expansion ($320,000)

The donation will triple the size of HSNY's annual scholarship pool, increasing available funds from $160,000 to $480,000. This expanded program will also open eligibility to international applicants for the first time, extending HSNY's mission beyond the United States to aspiring watchmakers worldwide.

“As the world becomes more digital and AI-driven, it’s more important than ever to celebrate and preserve human craftsmanship,” said Kyle Vogt, Executive Director of the Vogt Foundation. “We are pleased to be partnering with HSNY to support the next generation of watchmaking artisans and to recognize excellence in the field.”

“Education is the foundation of our mission at HSNY, and the Vogt Foundation's generosity enables us to extend that mission further than ever before,” said Nicholas Manousos, Executive Director of the Horological Society of New York. “By expanding our scholarships globally, we're not only supporting more students, but we're also strengthening the future of watchmaking as a whole.”

Independent Watchmaker Grant Program ($150,000)

The Vogt Foundation's gift will also help establish a new Independent Watchmaker Grant Program, providing direct funding to independent watchmakers for essential tools and approved startup expenses. Awards will be determined based on innovation, finishing quality, and design, with special consideration for complications and novel movements.

“The independent watchmaker represents the purest form of horological creativity,” Manousos added. “These artisans push the boundaries of what's possible in design and engineering. With the Vogt Foundation's support, HSNY can now give these talented individuals the resources they need to bring their ideas to life.”

Together, these initiatives represent a landmark moment in HSNY's ongoing mission to advance the art and science of horology.

For more information about HSNY's educational programs, scholarships, and grants, visit hs-ny.org.

About the Horological Society of New York

Founded in 1866, the Horological Society of New York (HSNY) is one of the oldest continuously operating horological associations in the world. Today, HSNY is a 501(c)(3) nonprofit organization dedicated to advancing the art and science of horology through education. Members are a diverse mix of watchmakers, clockmakers, executives, journalists, auctioneers, historians, salespeople, and collectors, reflecting the rich nature of horology in New York City and around the world. http://hs-ny.org

Reading Time at HSNY: You Don’t Need a Weatherman

This post is part of a series, Reading Time at HSNY, written by our librarians. Today’s post was written by Miranda Marraccini.

If you’re familiar with our library at the Horological Society of New York (HSNY), you might not be surprised to learn we have books in our collection about lathes, sundials, and mechanical singing birds. Maybe you’ve seen other articles where I even mention some of our more offbeat offerings, say, a volume about jukeboxes or a study of the Loch Ness Monster. But what about eyeglasses, thermometers, barometers, and weather vanes? All topics you can read about at our library!

Our collection is especially strong in the field of scientific instruments. Prominent watchmakers often manufactured other optical tools or measuring devices, and even if not produced together, these classes of implements were often sold by the same retailers. Basically, if you can craft minute metal pieces with the extreme delicacy needed to function inside a precise watch, you can make a fine telescope, say, or a really fancy thermometer.

Sometimes scientific functions can even be combined with time-telling in complicated watches. In fact, one of the most famous complicated watches of all time, the Leroy 01, contains a thermometer, a barometer, an altimeter, and a hygrometer among its 25 functions. This 2014 article from the National Association of Watch and Clock Collectors explains the story of the watch and includes a list of its complications, including Northern and Southern Hemisphere sky maps, local time in 125 cities, and time of sunrise and sunset in Lisbon.

Image 1

Image 2

Above, images from one book in our library, “La Leroy 01, Ultra Compliquée,” in French, show a secondary dial on the famed watch with nine indications (of the 25), including hygrometer, barometer, and thermometer. Image 1 shows the dial, and image 2 explains how the hygrometer works inside the movement.

The hygrometer measures humidity using an actual human hair–as anyone knows who has tried to attend a formal wedding in August, hair’s length changes with humidity. The alteration in length can be quantified and paired with an indicator ranging from zero to 100. At least according to my crude translation, this book also claims that blonde hair works better for measuring humidity, proving that blondes not only have more fun, they are also better meteorologists.

Because of the overlap between horology and scientific instrument manufacture, our collection contains a number of books about scientific instruments, particularly those that measure the weather, including “A Treatise on Meteorological Instruments” (a reprint of an 1864 volume); “English Barometers 1680-1860”; and the intriguingly named “Barometers: Wheel or Banjo.” (Why not both? You’ll have to visit our library to find out.)

In our archival collection, we hold the papers of the Henry J. Green Company, manufacturer of meteorological and scientific instruments. James Green and his nephew Henry J. Green were important barometer makers and sold to institutions like the U. S. Navy and the U. S. Weather Bureau. A generous relative donated the company’s papers to HSNY a couple of years ago.

James Green, an English immigrant, started manufacturing “philosophical instruments” in Baltimore in 1832 and moved to New York a few years later (and to Brooklyn in 1890). Green’s bread and butter was the mercurial barometer, in which the level of mercury in a glass tube indicates how strongly the atmospheric pressure is pushing down outside the tube. Higher air pressure generally means clearer weather, while low pressure means clouds and rain, and extremely low pressure, the kind that makes your ears pop, means you’re inside a hurricane. After manufacturing quite a lot of barometers, Green quickly expanded into thermometers, used for meteorology and in laboratories.

Image 3

Image 4

In 1877, the United States Signal Officer, part of the U. S. War Department, wrote to Green asking for a volume discount, and Green obliged (image 3). Prices ranged from $3.00 for a pocket thermometer ($2.50 with the discount) to $100 for an observatory barometer. Green and the Signal Officer, actually a series of officers and administrators, carried on a robust trade throughout the 1870s and 1880s.

In 1883, the Chief Signal Officer requested some custom glass bulbs and glass tubing for a type of thermometer called a Jolly air thermometer (it’s not particularly cheerful; just named after someone called Jolly). He included a sketch of what he wanted, with dimensions (Image 4). A later letter from Green shows a particularly elaborate Gilded Age letterhead, bearing an image of a medal that Green received at the International Fisheries Exhibition, a kind of World’s Fair in London in 1883 (Image 5).

Image 5

Image 6

Many of the letters in the collection are all obliging, full of praise for Green’s instruments. However, like any business, there were unhappy customers. In image 6, the Chief Geographer from the U.S. Geological Survey writes to Green: “I regret to say that the cisterns of two of the barometers sent me some time ago, are leaking so badly that the instruments are temporarily worthless…the loss of the observations will cripple our work.” He requests a new barometer “at once” and ends his letter “Hereafter I must beg you that you put your instruments in such order that difficulties of this kind will not arise as they cause very serious trouble.” I don’t know how this particular situation resolved.

In addition to the Navy and Weather Bureau, Green corresponded with the Surgeon General, U. S. Patent Office, U. S. Geological Survey, and university observatories across America and Europe.

By the 1950s, H. J. Green was manufacturing barographs, rain and snow gauges, anemometers, wind vanes, thermographs, hygrometers, evaporimeters, and psychrometers (no, none of those are made up). Did you know there was so much to quantify about weather? A midcentury catalog (image 7) shows two types of barometers, a mercurial barometer (contains mercury, obviously) and an aneroid barometer (one that doesn’t use any liquid inside). Another page shows wind velocity and direction indicators, including ornamental wind vanes at right (image 8). We might not think of weather vanes as scientific instruments, but they do report data about atmospheric conditions, namely, which way the wind is blowing.

Image 7

Image 8

Image 9

Another curiosity is a book whose title translates to “Church Steeple Weathercocks and Weather Vanes in Everyday Life and in Art History” (it probably reads better in the original German.) Josef H. Schröer, the book’s author, founded a museum of weather vanes from his own collection. His wife, Ina, writes in her foreword to the book that the “specimens” joined the family gradually over 40 years, and that over the course of that time “they…also crept into my heart!” I can see this must be true because the book also includes a poem on the same topic by Ina.

Ina Schröer goes on to discuss the Christian symbolism of roosters and why they appear on top of churches. Although the book is exhaustive, there isn’t a huge amount of variation among the vanes. There are a lot of roosters and crosses, with a smattering of other religious figures, like the archangel Michael battling Satan (image 9). I was surprised to discover, however, that the author included his own accomplished creations in another area: baking bread in the shape of weather vanes (image 10).

We’re verging on another subject here, the connection between horology and food, which I think deserves its own article. Let me know in the comments if you agree, because these scrumptious-looking bread chickens are making me peckish.

Image 10

Reading Time at HSNY: Ex Libris

This post is part of a series, Reading Time at HSNY, written by our librarians. Today’s post was written by Miranda Marraccini.

Have you ever looked at a book in your collection and thought, “I need to make absolutely sure potential thieves know this book is mine”? Or maybe just, “This book could use a little pizzazz”? If the answer to both of these questions is no, well, then we don’t have much in common. But if you’ve ever considered how to inscribe your books in a manner befitting your sparkling personality, then you might have something in common with both the author of this article and the former owners of books in our library at the Horological Society of New York (HSNY).

Although HSNY’s current collection is largely the gift of one generous bibliophile, Fortunat Mueller-Maerki, he bought most of his books secondhand. Many contain marks of their previous owners. I’ve often appreciated how these names and inscriptions add meaning to the books they adorn, telling stories about how people have used and loved them over the years. Most of the book traces I’ve written about previously have been handwritten, but in this article, I’ll focus on bookplates, which are printed expressions of ownership pasted to the inside of a book. Because our Jost Bürgi Research Library collection specializes in the study of time and timekeepers, former book owners sometimes bought or commissioned bookplates that incorporated horological themes.

Image 1

Of the bookplates I’ve snapped photos of, the one in image 1 particularly caught my eye, and you can probably guess why. It includes a six-pointed star, a naked woman tastefully framed from the back, and a number of symbols of the book owner’s interests including, clockwise from top right: a watchmaker’s lathe; violin and sheet music; executioner’s tools; escape wheel; quill pen; magic tricks; Egyptian symbols; a classical column; some things I can’t identify that look like fireplace tools; and a black cat with witch’s broomstick. The middle of the bookplate features the mysterious sator square, a Latin palindrome that has served as a mystical and religious symbol for hundreds of years. At the top and bottom of the central star, the Greek letters alpha and omega denote the Christian God.

Who, you might ask, was the owner of this book, apparently a person of myriad interests? Henry V. A. Parsell, Jr. was a multitalented Reverend (later Bishop), “electrical genius,” and engineer from a wealthy new-money New York family. He wrote a book called “Gas Engine Construction" and “made an exhaustive study of evolution, astronomy, archaeology, and many different philosophies,” according to a newspaper article about him. “Many different philosophies” included a now-defunct Masonic order called the “Egyptian Rite of Memphis,” which may explain the ancient Egyptian symbols in the image.

Parsell commissioned Jay Chambers, a well-known graphic artist and illustrator of the time, to design this bookplate–he was one of the three partners at the Triptych Designers of New York, named in the signature at bottom right. This bookplate is remarkably detailed and personal, even compared to others in our collection. I feel I know a little bit about the adventurous Mr. Parsell and I would like to know more, because he seems like an eclectic character, to put it mildly. More than that, though, I think this bookplate encapsulates the joy of our library collection as a whole: eccentric, multifaceted, varied, and strange.

Image 2

As you might expect, quite a lot of bookplates in our library contain imagery that reflects either the container (a book) or the subject (time). I’ve written about one before, a bookplate belonging to the late historian Silvio Bedini (image 2). It shows a person absorbed in study behind a chaotic rubble of books, with the motto “Satis Temporis Non Est Nobis” or “For us, there is not enough time.” Visitors to the library often ask me if I’ve read all the books in the library (ha!) or, if not, to estimate what percentage of the collection I’ve read. Readers, there is never enough time.

Gerald S. Ruscoe has gone a bit more obvious with his bookplate, in which an hourglass sits on a pile of books covered with vines (image 3). The text on the top reads “Books Span the Ages…” and also shows a lamp of knowledge producing smoke. Putting on my “professional bookplate critic” hat, I will say the design is a little tame. This book is comfortable resting on the shelf behind the couch. This book might be afraid of taking the subway.

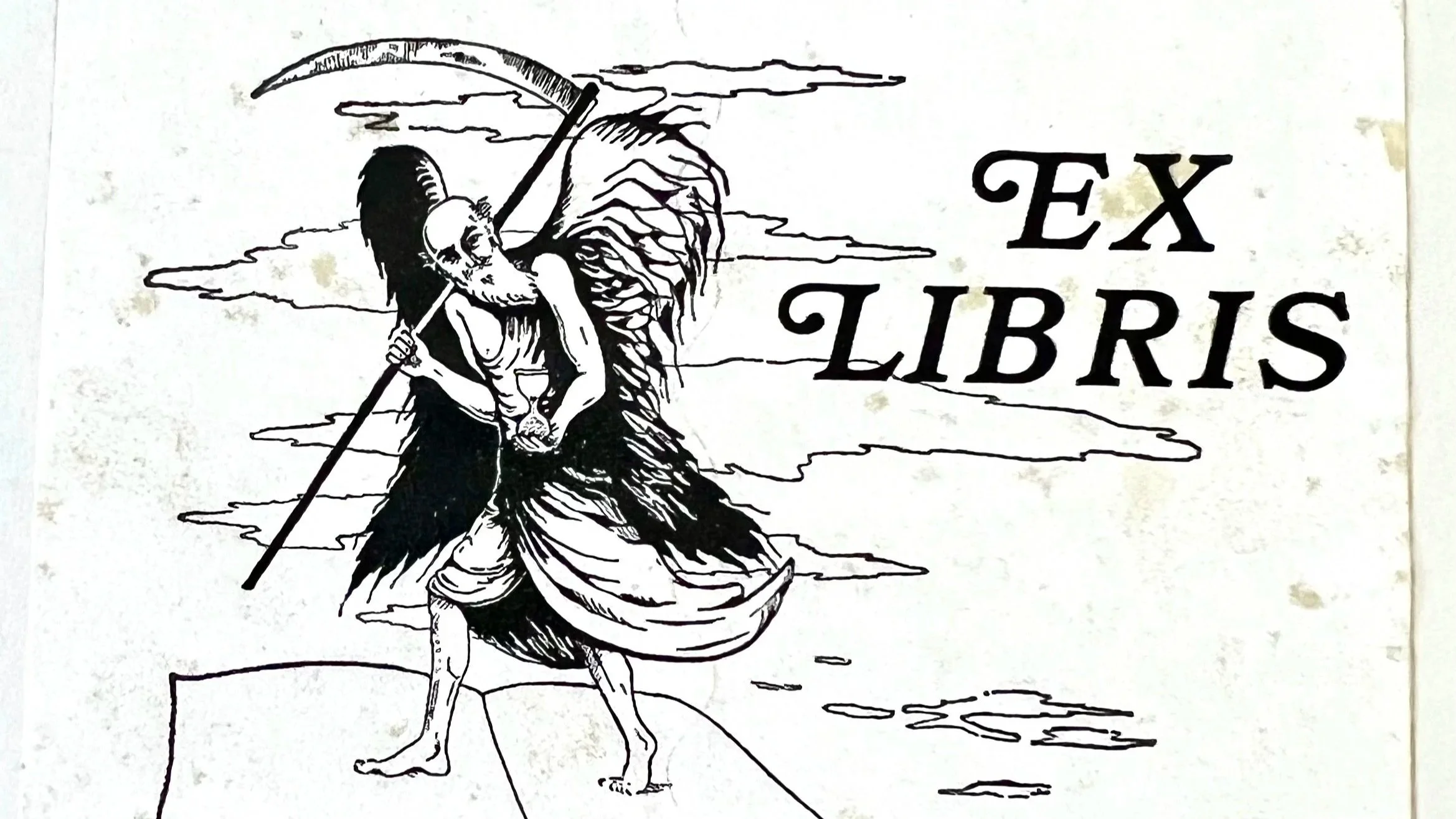

The same idea shows up in the bookplate of one F. L. Thirkell, although his imagery is more hardcore: Father Time shouldering a scythe, standing on the pages of a giant book that seems to be floating in the clouds like a sort of magic carpet of death (image 4). The bookplate says to me: your ride is here to take you away, and you won’t be coming back.

Image 3

Image 4

Thirkell was a Fellow of the British Horological Institute (BHI) who published in the BHI’s Horological Journal, including illustrated articles on how to repair specific models of watches. In my research, I didn’t find much about him as a person, but judging entirely from his bookplate, I would guess he enjoyed Black Sabbath (RIP Ozzy), gossiping with his pet rabbits, and scaring children with his Halloween decorations.

For the winner of the “most horological” award, I’d nominate the bookplate of Hugh L. Marsh, onetime treasurer of the National Association of Watch & Clock Collectors (NAWCC) (image 5). Marsh’s bookplate reproduces a hilariously over-the-top illustration from a late-17th-century book of fancy costumes.

Image 5

In the book, “Recueil les Costumes Grotesques et les Métiers,” each artisan wears the literal tools of their trade as clothes. For example, an apothecary walks around covered in bottles and funnels; a glass merchant dons mirrors and chandeliers. In this case, a watch-and-clockmaker wears, well, a ton of clocks. You can see the details better in the original image: he’s got chiming bells on his head, a coat festooned with dials and tools, and sleeves clank-clanking with watch cases at the elbows. It’s chaos. And, as two of my colleagues independently noted, it would make a great Halloween costume.

One of my favorites among the bookplates I discovered has absolutely nothing to do with time, books, or mortality. It’s a lovely Siamese cat, looking delightfully bemused to find itself inside “The Artistry of the English Watch.” As a cardigan-wearing librarian, I am, of course, a cat lover myself–I once acquired, in a white elephant gift exchange, a sign for my desk that reads “Ask me about my cats.”

Image 6

This cat bookplate belongs to Shelagh Berryman, one of the few female book owners represented in our collection (though many more are anonymous). A 1986 edition of The Music Box, an International Journal of Mechanical Music, reports that Berryman’s shop in the town of Wells contained the “second smallest museum in England”: “A large room above the shop…houses a collection of musical boxes of which browsers in the shop below who become entranced by the wonderful collection of goods on display for sale, may for a 50p fee, browse upstairs too. A demonstrator is present and these instruments are also for sale.” By 1988 Shelagh and her husband Douglas had expanded to a second shop in the bigger city of Bath, so they seem to have achieved a certain level of success.

Berryman owned at least two books in our collection, the other being “The Camerer Cuss Book of Antique Watches”. I like to think her bookplate expresses the multifaceted nature of many horologists, and in fact, most humans: sure, we’re watch people, but we can be cat people too. We have a sense of humor and whimsy about ourselves.

I’ll close with one last genre of bookplates I’ve noticed: messages to book borrowers. For example, the bookplate of George O. Keenan (image 7) contains a gentle warning: “I enjoy sharing my books as I do my friends, asking only that you treat them well and see them safely home.” Keenan, whom I couldn’t find much about online, clearly enjoyed lending volumes from his personal library to friends, as evidenced by the slip in this book. Evidently, he had no need to resort to a book curse to discourage thievery.

Image 7

Image 8

I’m not sure if anyone ever borrowed “United States Clock and Watch Patents,” but if you’d like to look at this very helpful reference work, you’re welcome to do so at our library anytime! And if you’re a member, you can even borrow it; just make sure to treat it well and see it safely home. Or if you prefer the more vulgar version, written in one of our other books owned by Cullen Tucker of Flemingsburg, Kentucky (image 8): “If this book should chance to stray kick it in the ear and send it home.”

For my part, I think my own fantasy bookplate design would feature some combination of my primary interests: tortoiseshell cats, fountain pens, watches, and of course, garlic (that last one might be a challenge to incorporate). What would your bookplate look like? Perhaps you already have one! If so, I salute you. I hope to see your bookplate proudly carrying your name into the far-off future, whether in our cozy library or as part of some distant collection, possibly in space, circling an unfamiliar star.

Reading Time at HSNY: Horology FAQ

This post is part of a series, Reading Time at HSNY, written by our librarians. Today’s post is by Miranda Marraccini.

In the course of my three-plus years welcoming visitors to our library at the Horological Society of New York (HSNY), I’ve developed a kind of intuition for the types of questions I tend to get asked, horological and otherwise. I don’t want to brag, but most people will get only a few words into their query before I have some idea of what they’re looking for and how to find it. After all, it’s my job, and I enjoy it immensely!

Not everyone can visit the library in person to politely pepper me with their inquiries, however. So this month, I’ve devoted my article to answering some of the most frequently asked questions I receive on a daily basis at the library.

Of course, you’re in front of a screen right now, so it’s possible you’ve already asked ChatGPT these questions. But if you don’t feel satisfied with the answers our robot overlord offers, why not take some advice from me, your friendly time librarian? I can guarantee you I’m not hallucinating. Here are 12 FAQs, one for every hour on the dial, in no particular order.

What is the number one book for a beginner in watchmaking?

It doesn’t get better than George Daniels’ “Watchmaking.” Daniels, probably the most renowned horologist of the 20th century, created a novel co-axial escapement that dramatically reduced the amount of friction produced as a watch runs, which, as my readers know, was a BIG DEAL. So he knew what he was talking about, to say the least.

In all, we have no fewer than 21 books authored, part-authored, or edited by Daniels. We have several copies of “Watchmaking” available at all times at HSNY, as well as “The Practical Watch Escapement.” Daniels co-authored the straightforwardly titled “Watches” with Cecil Clutton, which is an excellent illustrated historical overview of watch development.

Image 1: Dial decoration patterns from “The Magic of Watches” by Louis Nardin.

Daniels can be a dense read, though. If what you’re interested in is building your own watch, one option is “Beginner Watchmaking: How to Build Your Very First Watch” by Tim Swike. What I like about this very conversational book is that the author assumes zero knowledge and includes many large pictures. He introduces the reader to each part of a watch and includes quartz watches, which many authors don’t. Swike shows you how to find an affordable watch online and then customize it with a new dial, hands, band, or movement.

Another option for learning repair is the classic “The Watch Repairer’s Manual,” written by HSNY President Henry Fried in 1949 and still as relevant as ever.

If what you’re interested in is learning about watch collecting and the luxury watch industry, I recommend “The Magic of Watches” by Louis Nardin. Image 1 shows an illustrated page of dial decoration patterns you might find in high-end watches.

How much is my Rolex worth?

If you show me your wrist, I’ll make you an offer!

Just kidding. We don’t offer valuations. But your friendly librarians at HSNY are happy to help you research any brand or type of watch. For Rolex, some of our newer offerings are “Vintage Rolex: The Largest Collection in the World” and Mara Cappelletti’s “Rolex Philosophy.” For Patek, you might like to peruse John Reardon’s learned oeuvre.

But what’s the best watch? Should I buy a Rolex or Omega or Patek?

The best watch is the one you love, the one you’ll wear even when you’re not going anywhere but the bagel place, or even just sitting on the couch. I’ve got tiny vintage watches that spark joy every time I wear them, all bought for under $150. There really is no universal watch.

If you’re looking for a watch as an investment, one place to search is our collection of vintage price guides. You can find a watch that was collectible in 1989, and see how much it’s going for today. It’s probably faring better than your Beanie Baby collection.

I inherited a pocket watch from my grandparent. How do I find out more about it?

The internet can be really helpful for this kind of question, because enthusiasts make it their business to track down obscure makers and untangle convoluted industrial histories. I often refer visitors to the NAWCC members’ forum, where helpful horologists ask and answer questions about dial painting, electric horology, and even recovering stolen watches. The American Pocket Watch forum is especially active. I also recently discovered the Pocket Watch Database, which is very user-friendly for the non-initiated (like me).

If you’d like to bring your pocket watch (or pictures of it) into our library, we’ll do everything we can to help you learn more about the watch’s manufacture and its history. Our pocket watch section is robust, covering European and American models in detail. Reinhard Meis’ “Pocket watches : from the pendant watch to the Tourbillon” is pretty comprehensive.

How can I become a watchmaker?

“I like to take watches apart but I can’t put them back together.” That’s the line I hear most often from visitors at HSNY who are interested in learning more about watchmaking. There’s no need to struggle on your own, squinting at a diagram or advancing laboriously through a YouTube video frame by frame. (No shade to YouTube, still an excellent learning tool.)

You can get some hands-on experience in one of our classes, designed just for beginners. If you drop a screw, well, you won’t be the first or the last. A few classes won’t qualify you to be a watchmaker, however. Just like any career, if you decide you want to pursue watchmaking full-time, you can pursue a full-time certification program. There are nine US-based options for you, and we offer scholarships to all of them.

A classic horology textbook that we have in our library is “Theory of Horology,” always in high demand for watchmaking students and aspiring students. Also popular is the Joseph Bulova School of Watchmaking Training Manual.

I wear a smartwatch. Am I welcome here?

No, we’ll chase you off the premises. Yes, of course! In fact, my co-librarian, St John Karp, recently wrote an article about this very topic. Smartwatches have their place, and we even consider them a kind of gateway watch that encourages the wearer to try on other types of wristwear. You don’t need to wear a mechanical watch, an expensive watch, or any kind of watch at all to participate in our programming.

How can I get my watch repaired?

One option is to learn the basics yourself in one of our evening or weekend classes, described above, and repair it yourself! The books I recommended in the first answer will help you follow up and expand your knowledge.

As a nonprofit, we do not endorse specific businesses. A good resource is the American Watchmakers-Clockmakers Institute’s “Find a Professional” website, where you can do your own research. You can enter your ZIP code and get a list of watch and clockmakers in your area, sorted by specialty.

What do you do here?

As a librarian, I help answer people’s questions about watches, clocks, calendars, navigation, sundials, and many other topics related to time and timekeeping. Alongside my co-librarian, St John, I choose new books to add to the collection; organize our ephemera, books, and catalogs; and write about the library, along with other outreach.

You’re welcome to come to the library to conduct your research, or email us with questions at library@hs-ny.org. And if you just want to browse and admire the view of 44th Street from our spectacular windows, feel free to stop by for that reason too!

I spoke in detail about the job of a horological librarian on a 2023 episode of “The Waiting List,” a watch collecting podcast. Some of the information about HSNY is now outdated, but if you’re the type of person who wants to get into the weeds about Library of Congress classification, you’ll enjoy this chat.

What is longitude and how is it related to time?

It’s a long story (har har.) Dava Sobel’s “Longitude” is still one of the most important works on this topic, and we have several editions of the book, including an illustrated version and translations in German, French, and Italian.

Basically, the very short version is that before the late 18th century, European mariners had limited options for figuring out longitude, their east-west position as they crossed oceans. Lots of them died of scurvy in the middle of the vast watery expanse. The British government (among others) offered a prize for determining longitude, which eventually led to the development of the marine chronometer. This device could tell time at sea precisely enough to calculate distance traveled, which in turn allowed the determination of a ship’s longitude.

For more, check out this article I wrote a couple of years ago that illustrates the race to develop the marine chronometer with contemporaneous books.

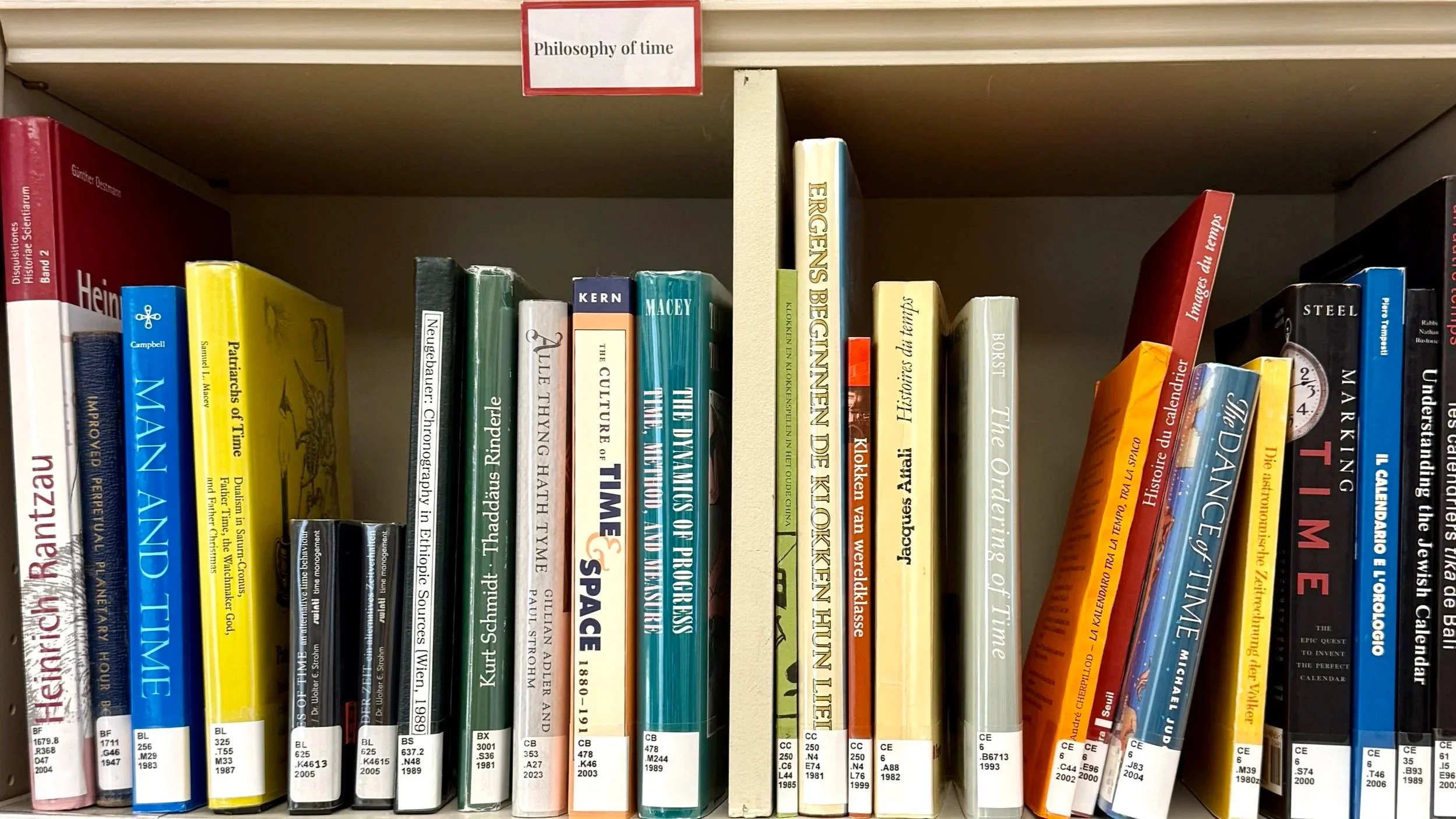

What is time?

Image 2: “The Book of Time” by Gerald Lynton Kaufman.

My colleague St John asks this question every time a physicist stops into the library and reports getting this answer back: “We’re working on it.” But if you’re interested in exploring this big question, we do have several sections of the library where you’ll find relevant information, including our philosophy shelves. That’s where we keep books with titles like “Travels in Four Dimensions”; “Time, The Familiar Stranger”; “A Watched Pot: How We Experience Time”; and of course, “What is Time?” (two different books). Image 2 shows a particularly attractive book jacket design for “The Book of Time,” which covers no less than eight dimensions, “proving that Time does not exist, and also that Time always exists.”

Why does a clock have 12 hours (or 24)?

I’m also going to leave this explanation to St John. He reports that in her essay in the 2001 book “The Discovery of Time,” Harvard scientific instrument curator Sara Schechner unearths an answer. In St John’s words, “the Egyptians recognized 36 time-telling stars, of which only about 12 were visible on a given day, so the night was divided into 12 parts based on the rising of these stars. This led them to divide the day into 12 parts as well… The 24-hour day then reached the Babylonians, then the Greeks.”

As far as “the subdivision into 60 minutes and seconds,” according to St John’s research, that comes from Mesopotamian mathematics. The Mesopotamians “hadn't invented fractional numbers, so they favored whole numbers that were most divisible without leaving a remainder (60 can be evenly divided by more numbers than 100).”

When was the first clock invented?

It depends on what counts as a clock! Is a sundial a clock? What about an hourglass? It’s all a little hazy that far back, but the earliest time-telling mechanisms (probably water clocks) are several millennia old, while the earliest mechanical clocks that we might recognize as clocks today were probably built around 1300. That’s when clockmakers developed the weight-driven movement in which the release of power is regulated by an escapement.

We’ve got quite a few books that cover the development of the clock, but some of the most fun to read are “Hands of Time” by Rebecca Struthers (which covers the history of time measurement broadly, in an inviting tone) and “About Time: a History of Civilization in Twelve Clocks” by David Rooney.

Of course, this is only a small sampling of the help we provide at HSNY. You might have something incredibly obscure on your mind, and if so, we would welcome the challenge of hunting down that information! If you need to see a Seiko watch parts interchangeability list from 1972, we got you. If you need to look up a 17th-century apprentice in the Worshipful Company of Clockmakers, we can hook you up.

Is there anything else you’d like to quiz us about? If so, you can stop by our library in person or ask your question by email at library@hs-ny.org. No question is too obvious, or too weird, to receive a warm welcome in our inbox.

Reading Time at HSNY: Life in The Loupe

This post is part of a series, Reading Time at HSNY, written by our librarians. Today’s post was written by Miranda Marraccini.

The Horological Society of New York was founded in 1866 by watchmakers for watchmakers–a community in which members leaned on each other if they got sick or needed help. As the Society grew and flourished, this element receded into the background. HSNY stopped providing sick benefits to members in the early 20th century. Although members continued to support each other in an informal way, their connections are not always visible decades later, through the obscuring screen of time.

In the late 1930s, HSNY began publishing the The Horologist’s Loupe, a newsletter for members keeping them informed about the Society’s events, as well as general developments in horology (many past issues are available on our website, and the originals reside in our library). Recently, with the help of our summer intern Michelle Julien, I read through some early issues of The Loupe as part of a project to better understand the Society’s history. As I read, however, I found that the contents of The Loupe were more personal, and more revealing, than I thought. I saw threads emerge–social threads. There was tragedy, celebration, consolation, and even a little mystery. Men took vacations and wives. They went to war and came back. They lost sons.

From the earliest days of The Loupe, the newsletter mentions casual social gatherings. Outside of the “smokers,” “banquets,” and more formal events that I’ve written about in previous articles, HSNY members liked to just hang out! In September 1938, “after the meeting about 45 members gathered for a congenial hour around a glass of beer and sandwiches in a nearby restaurant and thus were given an opportunity to meet friends and renew contacts” after the summer break.

In summer, particularly, The Loupe is full of bucolic vacation news. Members relax in Europe, Mexico, and more locally in upstate New York. When Barny Goldstein visited the Rockies on vacation, the editor made a joke about his “energetic” collecting habits, writing, “If one should suddenly encounter a 13,000 foot peak obstructing 59th street approach to the Queensboro Bridge, it should be sufficient notice to all that Barny is back (not empty-handed).”

Image 1

Image 1 shows an original cartoon titled “Summer Time in the ‘Catskills’,” at the time a popular vacation destination for New Yorkers. In the cartoon, a man and a woman relax in a canoe, possibly at sunset, while the man sings a guitar ballad. The woman looks enchanted, her arm loosely dangling into the water. Emerging from the lake like an amphibian, a young man wearing a loupe peers at her wrist. Below the waterline, one fish remarks to the other “he’s a watchmaker on vacation!” I think the joke is that a watchmaker is never truly on vacation because he always finds a watch to work on somehow.

These vacation reports, full of inside jokes, demonstrate how well HSNY men knew each other (see another example, image 2). In summer 1949, Orville R. Hagans went on a fishing trip, and Barny Goldstein, serving as temporary editor, reported teasingly: “the wire service is very accurate in advising re Mr. Hagans’ negative catches!” Goldstein must have regretted his snarky tone, because in our copy of the issue, he added a signed note to this item that reads “I apologize – 22″ worth.” Orville showed him up with a pretty big catch!

Image 2

Speaking of a good catch, another category of joyful article in The Loupe is the wedding announcement. In 1949, the editor reports that “Ben Cohen took unto himself a bride” and wishes him “best of luck and happiness, Ben!” In 1961, the editor asks playfully: “Congratulations to Leonard J. Oppenheimer, to be married November 12, 1961. Are you going to show us your new bride?” After weddings, naturally, children are born, and the community offers its generous best wishes.

Members’ interest in their friends’ families doesn’t end after birth, though. Sometimes articles show up that tell us what members’ adult children were doing, either personally or professionally. In April 1952, the editor writes: “Mr. Klein showed some photographs from ‘Bill’ at the last meeting (taken in Korea)....he looks ‘grown up’....handsome and rugged.” Bill Klein, son of member Morris Klein, was in Korea because he was serving in the Korean War.

Throughout the 1940s and 1950s, regular reports in The Loupe covered members’ service in the Second World War and Korean War, respectively. In December 1945, a member “back from the army and now in mufti, was a most welcome sight…[he] was a horological technician while in the Army.” (“Mufti” is a slang term for civilian clothes I wasn’t familiar with.) In January 1946, the Society welcomed back another veteran who was “an instructor of instrument repairs” in the army and “now senior instructor at the Bulova Watchmaking School.”

In 1951, Private J. W. Mandelbaum was “too tired” to repair some of his fellow soldiers’ broken watches during basic training. In the same year, The Loupe printed an excerpt from a lively letter written by member Walter J. Reif, who was stationed on a ship off Italy. Walter made friends with the local watchmaker, despite the language barrier: “we got along with a two-language dictionary and a pencil” (image 3).

Image 3

As these snippets indicate, horological training served these men well both during their service and afterward, when they gained stable employment. I’ve written about veteran watchmakers before, but for the first time while reading The Loupe, I understood how service shaped HSNY. A significant percentage of men in HSNY were either servicemembers or the parents of servicemembers. The current of war runs through The Loupe and brings with it both anxiety and relief. Today, this legacy lives on in our free classes, memberships, and scholarship for veterans.

You might notice that I’ve been referring to members as men, and that’s because HSNY was an all-male organization for much of the 20th century, though women sometimes attended meetings and events. As early as 1946, a Loupe report notes approvingly that the “usual stag-like” demographic at a monthly meeting was “pleasantly interrupted” by women in the audience. These included “one female horologist who displayed a keen and genuine interest” in the technical topic of the lecture.

Naturally, with the passage of time, many members experienced family loss and grief, and they shared their burdens through the medium of The Loupe. In the October 1938 issue, there is the first appearance of an announcement expressing sympathy for a member “on the occasion of the untimely demise of his wife.”

More often, members are ill. It’s not unusual in The Loupe to read about someone’s “protracted illness” or surgery. What I find touching is that other members noticed when they didn’t see their friends for a while, and they would check on them and send updates. In February 1950, for example, “Mr. Foster Brown…was ill and Mr. Feller was requested to visit Mr. Brown and report if the society could be of some assistance.” Thankfully, in October 1951, he was looking “better than ever.”

Mr. Andrew Park (twice President of HSNY) had a turbulent health journey that weaves through the Loupe of the 1940s and 50s. In 1948, while President, he was “on his way to Europe for a much deserved rest.” He was “not feeling too well” but “still attending our meetings regularly” in March 1951. When he endured a “major operation” in fall 1951, the Loupe’s editor at the time reported on his recuperation, urging “hurry back Andy!” Park soon retired to Florida and died in 1953. The editor eulogized him as an “outstanding craftsman,” noting: “distance did not dim the affection of the membership for him.”

The “chatter column,” a regular feature during this period, reported not only major life events but also minor changes. For example, Henry B. Fried, HSNY President in the mid-1950s, was “putting on pounds” (image 4). I’m not sure if Fried had been ill or if this was an entirely unsolicited observation. Either way, I don’t think I’d want this level of detail memorialized in print, but then, members probably didn’t see The Loupe as something that would be scrutinized by researchers several decades later. To them, it was ephemera – a way to connect and share news of interest only to a small, comfortable in-group.

Image 4

Another similar column notes that “Felix Klein, with his leg in a cast, attended our last meeting. Undaunted by his cast, he was, as usual, hard at work. We all wish him a speedy foot healing.” There’s a bit of a wink in the phrase “speedy foot healing” but really, these columns are saturated with a touching level of genuine concern. These men cared about each other and formed a tight network. They visited and nursed each other.

Although this mode of mutual support was a serious business, reading The Loupe showed me that these men had fun together, too. Of course, there were the summer vacations mentioned above, but even at monthly meetings, the atmosphere was not all straight-laced. Sometimes, the merriment was horological: In October 1945, HSNY hosted a “gadget night”: “At this meeting all members are invited to bring their pet odd gadgets and little tools that should prove of unusual interest to all – some of our members have promised to display a variety of odd ‘gadgets’” (image 5). In the photo below the announcement, showing the previous month’s meeting audience, most of the attendees look far too serious to be fooling around with “odd gadgets”– though I see a few smirks.

Sometimes there is levity unrelated to horology. For instance, in early 1950, one member demonstrated a surprising talent: “Hofsommer is [a] speed chess champ. While a small gathering watched, Walter Hofsommer quickly check-mated all comers.” Hofsommer and friends didn’t just come to meetings to discuss watch repair. They came for the atmosphere, the chance to socialize among like-minded people.

Image 5

Image 6

A considerable amount of space is taken up in mid-1946 issues of The Loupe by the planning and execution of a trip to the Hayden Planetarium (now called The Rose Center for Earth and Space) at the American Museum of Natural History. Image 6 conveys something of the level of excitement for this excursion, including a drawing of the building and the exhortation: “This interesting meeting has long been planned–Lets see you all there!!” While it may seem quaint to plan an earnest field trip like this for a group of adults, we have to remember that the planetarium was only around 10 years old at the time; its state-of-the-art projector showed views of the universe that people couldn’t see anywhere else, in mesmerizing detail.

The Loupe supplied a vivid preview of the event: “the walls and ceiling of what a moment ago was a great domed room have disappeared and we are out-of-doors with the darkening heavens above us…taking our breath with their beauty, the stars come out!...an involuntary gasp of amazement rises from the audience…we enter that other world of the sky.” Despite the over-the-top prose, there’s a sense of real excitement among members to connect with something bigger than themselves. Over 225 people attended that month’s meeting.

Image 7

According to The Loupe, HSNY members also took part in another popular pastime: the movies. Hollywood came knocking in 1948, when Paramount produced the film “The Big Clock.” The studio apparently consulted with members of HSNY’s executive committee on the project. The Loupe credits the film for “making the country clock conscious.” In image 7, President Andrew Park presents some sort of “commendation” to Paramount representative Anita Colby, who was an actor and a studio executive (though not actually in the movie). Without spoiling the plot, the thriller does indeed include a big clock in a pivotal role (hint: someone hides inside). Today, HSNY performs a similar role in entertainment, with our Executive Director, Nicholas Manousos, recently advising HBO in the production of a clock-related storyline for The Gilded Age.