The Horologist’s Loupe

The Horological Society of New York's newsletter (and today blog!) began publishing in 1936, and is one of the oldest continuously running horological publications in the world.

Previous Lecture: Public Enchantment: A History and Case Study of a Tiny Mechanical Jewel-feathered Protagonist

Brittany Nicole Cox, Antiquarian Horologist (Seattle, Washington)

May 1, 2023

Video recordings of lectures are available immediately to HSNY members, and the general public with a two-month delay.

Photography by Bryan Bedder

Reading Time at HSNY: Kids Talking Time

This post is part of a series, Reading Time at HSNY, written by our librarian, Miranda Marraccini.

Those of you who have been following my posts about our collection at the Horological Society of New York (HSNY) will know that as a librarian, I’m preoccupied with marks in books. I don’t disapprove of them–in fact I think they add immeasurably to the story of these paper objects and the people who loved them. At HSNY, we have lots of books that show traces of their owners, but the most adorable are the scrawls, signatures, and doodles left by children.

Image 1

One very well-loved children’s book in our collection is “Rollo’s Experiments” (1841). It stars the eponymous farmboy Rollo, seven years old, curious about everything, and quite easily distracted. The author, Jacob Abbott, wrote 14 Rollo books and they were popular enough at the time to have parody versions that skewered contemporary political figures.

We know a child read this copy of the book (or at least used it) because someone has colored in all the woodcut illustrations with what looks like a pastel crayon (see Image 1). Even though it’s sticky and comes off everywhere, this crayon is the charming evidence of how the book lived. Our copy is also signed in neat pencil by two girls, Sophie and Ellen Sword, possibly sisters.

In the chapter titled “Horology,” Rollo, playing in the sandbox with his brother Nathan, decides to make an hourglass. He quickly tires of this project because it involves washing and drying dirty sand. But then in the next chapter, Rollo’s father’s “hired boy” Jonas, who is a bit older, decides to make a sundial. In speaking with different adults in the story, Rollo and Jonas learn how to draw a meridian line, how to find the North Star, and how to build a gnomon (the triangular blade of the sundial that casts the shadow). In image 2, colored in by our eager reader, Jonas and Rollo work on their sundial, which is made out of some spare fence posts.

Image 2

Although “Rollo’s Experiments” was first published in 1839, it reads like any modern kids’ book. A blurb from The Mother’s Magazine, originally printed in the front of the book, says, “[Abbott’s] boys and girls talk and act like boys and girls, not miniature men and women.” Their dialogue and behavior still rings true today. The boys learn about how to create a sundial by building one, with gentle guidance from Rollo’s older, logically-minded sister, from patient adults, and from other books. They don’t understand everything, they make mistakes, and they get distracted and forget about their experiments. Rollo never finishes the hourglass. He gets a time-out for fighting with his little brother. And as he learns, the children reading learn along with him.

Another book in our library with annotations by a child is “Industrial Curiosities: Glances here and there in the World of Labour,” published in London in 1880 (our copy is the 1891 edition). One of my previous posts focused on a similar encyclopedia of the trades owned by generations of women in a family, some of whom signed their names in the book as children. “Industrial Curiosities,” as in that case, is not a book specifically written for children. This book has different sections explaining the history of various industries, like leather, perfumes, and even “seals and sealskins.” We own a copy of the book because of its long section about clocks and watches.

The end of the 19th century was a time of major change in horology, when watches were beginning to be produced in factories by machines, instead of in small workshops by hand. Pocket watches became more attainable and eventually ubiquitous. Alexander Hay Japp, the author of “Industrial Curiosities,” writes, “the penalty the City-man pays for the keyless gold repeater in his pocket is that he has lost the simple faculty…of reading time by the sun.” Sound familiar? Replace the word “keyless gold repeater” with “phone” and “sun” with “watch.”

Japp gives a vivid picture of the recent mechanization of the American watch factory. His description, which he quotes from an article by the women’s labor activist Emily Faithfull, makes no secret of the fact that children were working in the National Watch Company factory in Elgin, Illinois.

When drilling holes in the mainplate for screws, “a little girl cuts them with a needle-like drill, which revolves like lightning…another girl, with a chisel, whirling with equal rapidity, cuts away the ragged burrs or edges.” In the train room, a “girl in charge” cuts the teeth of wheels. “Nimble-fingered girls” also work in painting dials, engraving parts, inserting mainsprings, and in manufacturing the 44 screws needed to assemble each watch.

Some of these girls were young adults or older teens, but some were children (“little girls” as well as boys) working with heavy machinery in dangerous conditions. A girl in the electroplating room in Elgin “was kept at home for three weeks, with sores upon her hand” caused by contact with the “deadly poison” solution. Their work prefigures the “Radium Girls” of the 20th century, who painted dials with poisonous radium, one of whom is now honored by a scholarship at HSNY.

Image 3

Our copy of “Industrial Curiosities” contains this pencil drawing of a man in a hat and a woman in a triangular dress holding hands (Image 3). The woman has curly hair and no fingers, while her companion has all his fingers and is leaning on an unidentified stick-like object. A child took this book off the shelf and (perhaps sneakily) added their own unique touch. This sweet little drawing is a reminder that the kids in these books, and the kids who read them, were real people with individual struggles, quirks, hobbies, and triumphs. “Rollo” and “Industrial Curiosities” together show a range of experiences for kids of this period: working as a hired hand, working in a factory, hanging out on a farm, learning science at home.

Image 4

At HSNY, in addition to these old, much-loved books, we have a whole collection of modern juvenilia, which is the formal library way of saying children’s books (though I prefer the latter). There are classic favorites for chapter-book readers like “The Time Garden” by Edward Eager (1958), in which a group of kids travel through time with the help of a talking toad and a magical sundial in a thyme garden (get it?). In Lloyd Alexander’s “Time Cat” (1963), a cat named Gareth leads his boy on a journey through nine lives over thousands of years. And of course we have a few copies of the first Nancy Drew story, “The Secret of the Old Clock”, an exciting tale involving a missing will, hostages, and a car chase (1930). In a more recent favorite, Brian Selznick’s “The Invention of Hugo Cabret” (the basis of the movie “Hugo”) a young French boy repairs clocks and automata and solves a mystery. This book is filled with beautiful, textural pencil drawings like the one in image 4.

We also have a selection of interactive picture books that help kids learn how to tell time on an analog clock (Image 5). It’s a skill that not all kids know in a digital age, but these books make it fun.

Image 5

Although I’m not officially suggesting that kids in our library can write in the books, I wholeheartedly invite them to visit us and enjoy the collection in whatever way makes sense to them. Families are more than welcome. We’re open on weekdays, 10AM-5PM, and we do have stickers!

Reading Time at HSNY: It’s Complicated - Time and 18th Century Navigation

This post is part of a series, Reading Time at HSNY, written by our librarian, Miranda Marraccini.

Image 1 – Diagram from Mårten Strömer, Aequatione Temporis (1749)

Image 2 – From Richard Burroughs, A Treatise on Trigonometry and Navigation (1818)

At the Horological Society of New York’s (HSNY) Jost Bürgi Research Library, we have at least 15 books from the 18th century – an era of explosive growth and lightspeed technical innovation for horology. Some of our most well-known horological manuals date to this period.

One of the jewels of our collection is a first edition of Ferdinand Berthoud’s 1763 work Essai sur L'horlogerie (You can view a copy held by the Getty Museum here). Berthoud, an important horologist in Paris, developed his own version of the marine chronometer, a game-changing device that eventually enabled people to determine longitude at sea. Although Berthoud’s invention is not the one credited as the first, it is one part of a fascinating story.

Before the mid-18th century, marine navigation was a serious problem. Mariners could determine their latitude by looking at the angle of the sun during the day or the North Star at night, but they couldn’t measure longitude in the same way. It was, for centuries, an unsolvable puzzle, but navigators did the best they could by using dead reckoning, basically a form of guessing based on an estimate of speed. They also used complicated navigational tables and celestial charts to try to work out longitude.

The mathematical method took an enormous amount of calculation. In The Mariner’s Compass Rectified (1750), Andrew Wakely writes in his preface about compiling the data for the book: “my Labour was so great, that I almost fainted.” This book, which we have in our collection at HSNY, was written by two mathematicians and published by a printer in London “where you may have all Sorts of Sea-Books,” showing that math and horology were intrinsically tied to navigation. Below, two somewhat crude illustrations from The Mariner’s Compass nonetheless demonstrate effectively how to use two basic navigational instruments, the fore-staff (image 3) and the quadrant (image 4).

Image 3

Image 4

During the course of the century, there was constant debate about how to improve navigation. Some mariners maintained that they needed to be able to tell time at sea so that they could calculate how far they had traveled from their starting point – for British sailors, that would be Greenwich, as in Greenwich Mean Time. But many still believed navigation should be improved by advances in astronomical calculation, rather than the invention of new timekeeping devices.

Long pendulum clocks, which were the most precise means of keeping time on land, wouldn’t work on a ship that was in constant motion. And although spring-driven clocks had been invented in the late 17th century, they too could be affected by a ship’s movement, as well as factors like temperature (which can cause metal to expand and contract), pressure, and corrosion. So horologists had to come up with something new. The British government even established a Board of Longitude to administer a prize worth up to £20,000 (equivalent to millions in today’s money) for a workable idea.

A number of people tried to solve the problem in novel ways. One theoretical solution was published in the Gentleman's Magazine in 1737, an issue that we have in our library (image 5). The article about the “important secret of the longitude” is signed only “The Farmer.”

Image 5

“The Farmer” describes a new clock called the Perpetual Motion that he developed based on the previous work of his “most ingenious” friend, the horologist Joseph Williamson. The author claims it is so precise it will only gain or lose four seconds in a month.

Though it’s essentially still a pendulum clock, with some improvements, the author claims that if the clock is hung on a ship so that it remains perpendicular at all times, “the motion of the sea will not affect it.” A heavy weight attached to the bottom of the case will “master all Shocks.” This seems doubtful, but the author, citing no less of an authority than Sir Isaac Newton, points out that because of the Earth’s revolutions, “our Clocks on Shore are turned Topsy-turvy every 12 hours,” and they still keep time! He seems to recognize that his case isn’t entirely convincing, and recommends that ships carry “a good Spring-Clock” and “good Watches” as backup, to be reset daily according to the “Perpetual Motion.”

At the end of the article, the editor responds with an acknowledgment of the proposal’s flaws, and an invitation: “And now I ask, whether a better can be framed, and challenge the whole World to produce it.” The horologists of the world, particularly Ferdinand Berthoud, British carpenter John Harrison, and French clockmaker Pierre LeRoy, were working on it.

By the later 18th century, the science of celestial navigation had progressed somewhat, and mariners were starting to use the lunar distance method for figuring out longitude. This series of celestial calculations was first theorized more than 200 years earlier, but not published and popularized until 1763. One of our books, Epitome of the Whole Art of Navigation (1782), promises to teach the lunar method, as well as everything you would need to become a “complete NAVIGATOR,” including lots of logarithmic tables. The primary author is James Atkinson, who also co-wrote the Mariner’s Compass earlier in his career.

Image six shows one of several fold-out maps and charts in this book, along with a diagram of longitude and latitude at left.

Image 6

Image 7

Someone named Samuel Carrington owned this copy, and signed it very neatly in 1784, just a couple of years after it was printed (image 7). It’s a common name, but I did find one record of a London shopkeeper, Samuel Carrington, who testified as a witness to an attempted murder in 1828. It may be our book’s first owner!

The lunar distance procedure described in Epitome of the Whole Art of Navigation caught on quickly. We have another book published around the same time in Utrecht, in French, that discusses the same method. Mariners continued to use it even after the chronometer was invented, because it was cheap and accurate enough for shorter journeys.

Image 8

Finally, John Harrison developed several working prototypes of the marine chronometer, culminating in the H4 in 1761, which served as the basis for improvements by LeRoy and Berthoud, among others. While building his earlier models, H1 through H3, Harrison developed a series of complicated inventions meant to compensate for movement and changes in temperature at sea. In H4, he finally abandoned these, developing a small spring-driven movement with a balance wheel that could oscillate at a higher frequency than the balance wheel in a normal watch, which made it much more usable on a ship. The images below show postcards in our collection from the Royal Observatory and the National Maritime Museum, both in Greenwich, England. They depict John Harrison (image 8) along with his four prototype marine chronometers, H1, H2, H3, and H4 (image 9).

Image 9

As further improvements made marine chronometers more precise, reliable, and affordable, adoption surged. By 1820, enough people had tried out the new chronometers for George Fisher to publish Errors of Longitude, a book in our collection which includes tables laying out how far different expeditions had deviated from their intended course. Fisher calls chronometers “almost indispensable articles” in the “present improved state of navigation,” but seeks to improve their function for the future through detailed observation. And indeed marine chronometers continued to serve their indispensable purpose until the 1960s, when they began to be replaced by electronic systems and eventually GPS. Here at HSNY, we have an American marine chronometer made by Elgin from the 1940s in our permanent collection. For more about marine navigation, library visitors can peruse our modern books on the subject, including Dava Sobel’s Longitude: the True Story of a Lone Genius who Solved the Greatest Scientific Problem of His Time and even kids’ books like The Discovery of Longitude by Joan Marie Galat and The Longitude Prize by Joan Dash.

It would be difficult to overstate the importance of the marine chronometer. It completely changed the course of navigational history, and history in general. Because it allowed mariners to navigate accurately over long distances, it contributed to the dominance of the British Royal Navy and all of the consequences of colonization. This complicated legacy plays out over the history of modern horology, driving the perpetual motion forward, over the horizon, tick by tick.

Upcoming Lecture: Public Enchantment: A History and Case Study of a Tiny Mechanical Jewel-feathered Protagonist

Brittany Nicole Cox, Antiquarian Horologist (Seattle, Washington)

May 1, 2023

Birds are a wonder, not just for their vocal abilities or their powers of prediction, but for their biology. The iridescent colors some feathers generate are the result of the refraction of light. A bird's feathers weigh more combined than its skeleton. A bird is capable of singing two notes simultaneously. Mankind has attempted for centuries to emulate their song and their beauty. The mechanical singing-bird tabatière was born during the late 18th century and continues to enchant today.

At the May lecture of the Horological Society of New York, Brittany Nicole Cox will examine the history behind the lineage of the mechanical singing-bird along with a case study.

Special thank you to the Toledo Museum of Art for allowing Brittany Nicole Cox to share this talk. Photo credit Ben Lindbloom.

*Doors open at 6PM ET, lecture to begin at 7PM ET. RSVP is required.

** The lecture video will be available to members immediately, and to the general public following a two-month delay.

HSNY Awards $125,000 in Financial Aid at Its Annual Gala (Pics)

Lifetime Membership Card Sells For Record-Breaking $20,000

The Horological Society of New York (HSNY) held its 157th anniversary Gala & Awards Ceremony on Saturday, April 15, 2023, where it awarded a record-breaking $125,000 in financial aid to 20 watchmaking students and four U.S. watchmaking schools, and raised an additional $25,000 toward its mission to advance the art and science of horology.

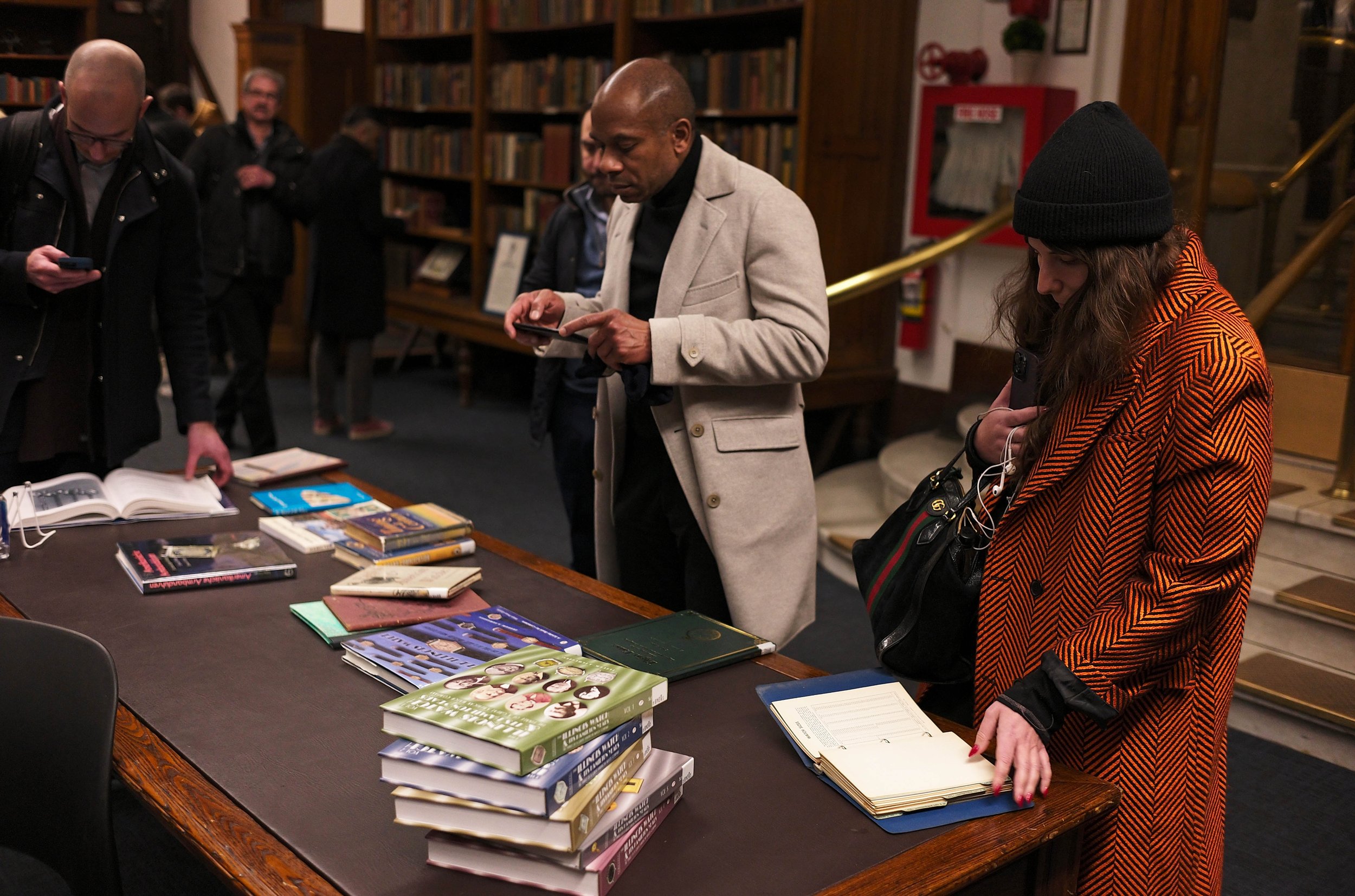

Mingling in Harvard Hall!

The historic Harvard Club of New York City served as the backdrop of HSNY’s gala once again, where 270 guests from around the world gathered to toast to one of the world’s oldest continuously operating horological associations and support the newest generation of watchmakers with scholarships.

“The 2023 gala broke records in every way for the Horological Society of New York,” said Carolina Navarro, HSNY Deputy Director. “An increasing demand to attend allowed us to max out capacity and draw crowds from top watch brands, VIPs, influencers, and even celebrities, who showed up in style to support our now 157-year-old society.”

At the gala, HSNY presented its largest offering of financial aid to date, and awarded more students than ever before.

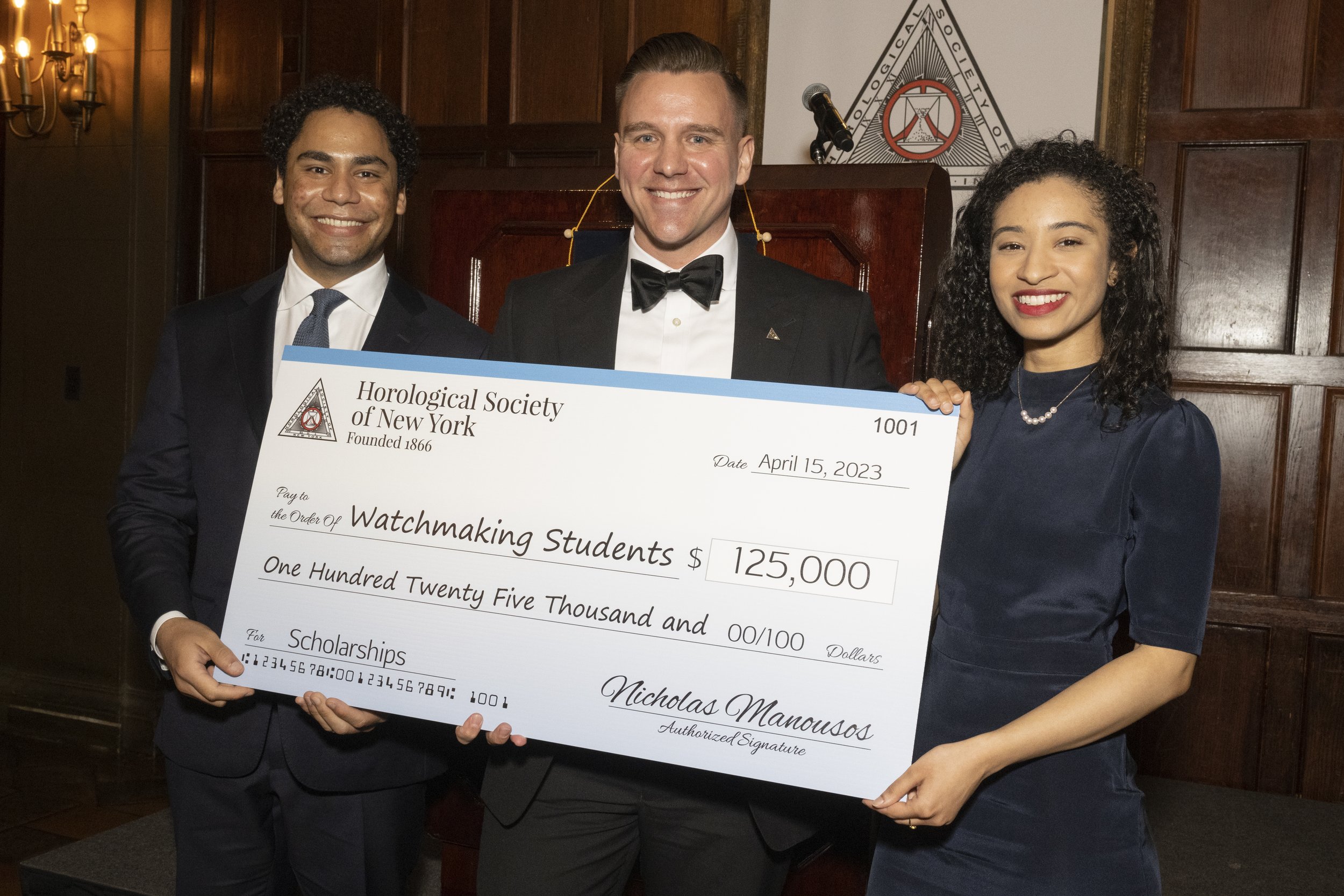

Steve Eagle, HSNY’s Director of Education, presented a ceremonial $125,000 giant check to Mary Raso, student at the Lititz Watch Technicum, and Jose Weinberger, student at the Nicolas G. Hayek Watchmaking School, who accepted the award on behalf of all recipients. (Please see below a full list of financial aid recipients.)

HSNY Executive Director Nicholas Manousos delivering opening remarks.

Watchmaking students Jose Weinberger and Mary Raso accept a ceremonial $125,000 check on behalf of all 2023 recipients. A giant check was issued by HSNY Director of Education Steve Eagle, center.

“For context, in 2017 we awarded one scholarship to one student, and this year we awarded 20 students and four schools,” said Nicholas Manousos, HSNY Executive Director. “This is made possible through the generous donations from our sponsors, our dedicated members, and gala supporters.”

Earlier this year, HSNY introduced three new financial aid opportunities for watchmaking students across the country — The Charles London Scholarship for Watchmaking Students, The Charles Sauter Scholarship for Innovation in Horology, and The Simon Willard Award for School Watches.

Isabella Proia of Phillips in Association with Bacs & Russo accepting a bid for the HSNY 2023 Lifetime Membership Card.

Benjamin Nelson, winner of the HSNY 2023 Lifetime Membership Card.

Additional highlights from the evening included the sale of HSNY’s 2023 Lifetime Membership Card, auctioned by Isabella Proia of Phillips in Association with Bacs & Russo. A long bidding war for the sole lot of the evening echoed throughout the Harvard Club’s Main Dining Room, ending in a hammer price of $20,000. The card, which was engine turned by Joshua Shapiro and hand-engraved by Artur Akmaev, will grant top bidder Benjamin Nelson lifetime membership privileges at HSNY, including all aspects of current and future membership tiers. Proceeds from the sale benefit HSNY’s ongoing financial aid initiatives. HSNY’s 2023 Charity Auction will be held online in June and will be hosted by Phillips in Association with Bacs & Russo.

Dinner came to a close with Aldis Hodge — horologist, HSNY Trustee and Hollywood actor — calling for additional donations to kickstart the 2024 financial aid season. In total, the Society raised $25,000 throughout the evening.

The gala concluded with the reopening of the picturesque Harvard Hall for after-dinner drinks, a large spread of French pastries, and live music.

Horologist, HSNY Trustee and Hollywood actor Aldis Hodge calling for donations to kickstart the 2024 financial aid season.

Guests enjoying desserts and after-dinner drinks in Harvard Hall.

Gala attendees posing with a sweet treat of the evening — HSNY branded chocolate bars!

Teddy Baldassarre, Kevin O'Leary and Linda O'Leary enjoying the evening.

A red carpet moment upon arrival!

HSNY thanks all participating brands, sponsors, members and guests for their support! A save-the-date for HSNY’s 2024 Gala & Awards Ceremony is coming soon!

HSNY 2023 Financial Aid:

The Henry B. Fried Scholarship for Watchmaking Students ($5,000 each)

Adam Barry (Paris Junior College Watchmaking Program)

Kent Beckley (North Seattle College Watch Technology Institute)

Alex Ciesielski (Lititz Watch Technicum)

Samuel D. H. Mallow (North Seattle College Watch Technology Institute)

Andy Park (North American Institute of Swiss Watchmaking)

Jonathan Vasquez (Nicolas G. Hayek Watchmaking School)

Kevin Zamani (North Seattle College Watch Technology Institute)

The Benjamin Banneker Scholarship for Black Watchmaking Students ($5,000 each)

Mary Raso (Lititz Watch Technicum)

Jose Weinberger (Nicolas G. Hayek Watchmaking School)

The Grace Fryer Scholarship for Female Watchmaking Students ($5,000 each)

Ariane Anderson (North American Institute of Swiss Watchmaking)

A Reum Im (North Seattle College Watch Technology Institute)

Vanessa Loor (North American Institute of Swiss Watchmaking)

NEW IN 2023 The Charles London Scholarship for Watchmaking Students ($5,000 each)

Ryan Austin (Lititz Watch Technicum)

Tanner Caraway (Veterans Watchmaker Initiative)

Michael Davanzo (North Seattle College Watch Technology Institute)

River Pryor (North American Institute of Swiss Watchmaking)

Harrison Siegling (Lititz Watch Technicum)

The Howard Robbins Award for Watchmaking Schools ($25,000 in total)

Gem City College School of Horology ($7,500)

Veterans Watchmaker Initiative ($7,500)

North Seattle College Watch Technology Institute ($5,000)

Paris Junior College Watchmaking Program ($5,000)

NEW IN 2023 The Charles Sauter Scholarship for Innovation in Horology ($5,000 each)

Nicholas Chin (Lititz Watch Technicum)

Thomas Dunphy (Lititz Watch Technicum)

The Oscar Waldan Scholarship for Jewish Watchmaking Students ($5,000 each)

Chris Tullos (Veterans Watchmaker Initiative)

# # #

ABOUT THE HOROLOGICAL SOCIETY OF NEW YORK

Founded in 1866, the Horological Society of New York (HSNY) is one of the oldest continuously operating horological associations in the world. Today, HSNY is a 501(c)(3) nonprofit organization dedicated to advancing the art and science of horology through education. Members are a diverse mix of watchmakers, clockmakers, executives, journalists, auctioneers, historians, salespeople and collectors, reflecting the rich nature of horology in New York City and around the world.

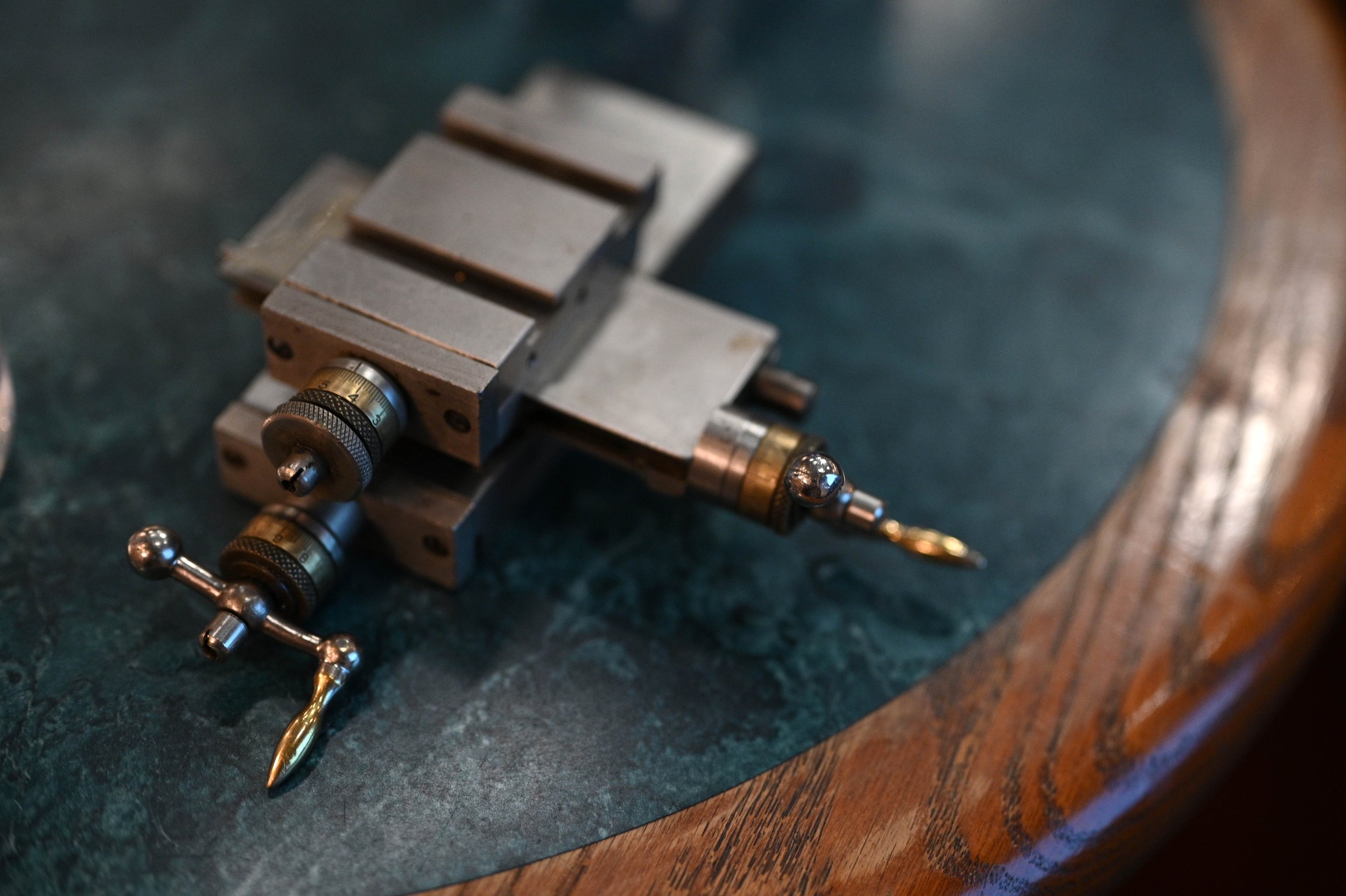

HSNY 2023 Lifetime Membership Card To Be Auctioned by Phillips in Association with Bacs & Russo at the Society’s Gala (April 15)

The Horological Society of New York (HSNY) introduced the creation and auction of a Lifetime Membership Card at last year’s gala. The tradition continues in 2023.

Fresh off the rose engine, HSNY’s 2023 Lifetime Membership Card is a new design once again engine turned by Joshua Shapiro and hand-engraved by Artur Akmaev. This Lifetime Membership Card grants the owner lifetime membership privileges at HSNY, including all aspects of all current and future membership tiers. The card is carefully crafted from a 92.5% sterling silver alloy with tarnish-resistant properties 4-5 times that of traditional sterling silver. The recipient's name will be hand-engraved once the auction is complete.

The Lifetime Membership Card will be the only item auctioned live at HSNY’s 2023 sold-out gala on Saturday, April 15, and will be hosted by Phillips in Association with Bacs & Russo. Last year, a friendly bidding war ensued with Jared Tramontano receiving the inaugural membership card.

Proceeds from the sale of the HSNY 2023 Lifetime Membership Card will benefit the Society’s ongoing financial aid initiatives and its mission to advance the art and science of horology.

Happy bidding!

Welcoming New HSNY Members, March 2023

HSNY would like to welcome the following new members. It is only with our members' support that we are able to continue flourishing as America's oldest watchmaking guild and advancing the art and science of horology every day.

GOLD

Kyle Hovis, NC

SILVER

Joey Richey, NC

BRONZE

Aaron Esraeilian, NY

Aaron Peltz, NY

Alain Troadec, FL

Alejandro Companioni, FL

Alex Feldman, NY

Alexander Lee, RI

Alexander Liebeskind, NY

Alwin Joseph, NY

Andy Lin, NY

Angus Russell, FL

Anney Norton, NY

Blake Allen, NC

Caroline Williams, CT

Chris Albee, NY

Chris Rowley, OH

Daghan Perker, NY

Daniel Holtan, VA

David Yue, MD

Denis Salle, HI

Dorrit Corwin, CA

Doug LaViolette, WI

Ellen Sorensen, NJ

Erik Kahn, NJ

Ezra Correa, UT

Flavius Cucu, WI

Iakovos Babalitis, VA

Ivan Brown, NY

James Barrett, NY

James J. Wilson, CA

Jay Doscher, CA

Jean Lhuillier, NY

Jefferson Lilly, CA

Jon-Paul Kraft-Goltz, MI

Lavi Rudnick, NY

Lawrence Heller, NY

Lin-Song Hsieh, VA

Mark Connolly, Ireland

Mason Neumann, CA

Matthew G. Ursch, IL

Maxwell L. Shillman, FL

Michael Dweck, NY

Michael Moses, Canada

Mike Ginese, NC

Nicholas Alexander Boos, NY

Owen Anderson, ME

Paul Capar, PA

Ray Clapp, TX

Richard Gorman, WA

Russ McCray, GA

Ryan Farr, UT

Ryan Zucchetto, NY

Sophia Kremer, NY

Stavros Gaitanaros, MD

Thomas Gilmore, RI

Tobias Asplund, CA

Todd Selig, NH

Viktor Bárdi, RI

Virginia Arakelyan, NY

Vivishek Sudhir, MA

William Brown, PA

William W. Ehrgood, OH

* Upgraded Membership Level

Previous Lecture: Collecting Vintage Watches, Part II

Eric Wind, Founder and Owner of Wind Vintage (Palm Beach, Florida)

March 6, 2023

Video recordings of lectures are available immediately to HSNY members, and the general public with a two-month delay.

Photography by Bryan Bedder

Reading Time at HSNY: Smokers, Banquets, Galas: Celebrating 157 Years of Horological Tradition

This post is part of a series, Reading Time at HSNY, written by our librarian, Miranda Marraccini. This article was co-written by HSNY’s Deputy Director, Carolina Navarro.

For 157 years, the Horological Society of New York (HSNY) has known how to throw a good party. On April 15, 2023, we’ll be celebrating at our annual gala at the Harvard Club of New York City, just across the street from our headquarters in Midtown Manhattan. It will be a night of tasty food, live music, and support for HSNY’s mission.

Our earliest club social events were “smokers” — not for smoking meat, as I originally guessed, but social events where men smoked tobacco, told jokes, and sang drinking songs in German. The songs were in German because the first members were German — the organization was founded in 1866 as the Deutscher Uhrmacher Verein (German Watchmakers Society). In the late 19th century, the Society went through different variations of German and English names, until 1930 when we adopted our current moniker. (We have a collection of HSNY gala programs and other historical documents at the Jost Bürgi Research Library.)

Image 2

One tradition has stayed the same — HSNY members have always celebrated with food. The earliest banquet menu in our archives is from 1912. Printed in German, it is an elaborate joke as it includes some standards like oysters, chicken, and Brussels sprouts, but also some curious items like “enamel filet with cuvette sauce,” “horological cream puffs,” “spindle clock cheese,” and under salads, “etched spiral springs with double-proofed acidic chronometer oil.” All of the delicious dishes involve puns on watch and clock parts. I’m not exactly sure what the men of HSNY did end up eating on March 5, 1912, but safe to say it wasn’t a plate of hairsprings. At right, image 2 shows a banquet menu from 1937 listing some more conventional menu items.

In 1916, the New York Watchmakers Society (as we were then calling ourselves) celebrated its 50th anniversary with both a smoker and a “Golden Jubilee” banquet. Attendees sang songs in English and German, with lyrics comparing the organization to a well-constructed clock that has run for 50 years.

Though the smoker was the traditional men’s-only celebration, the banquet was not: “this invitation/ Means the ladies too, / Trusting in your expectation/ A jolly time for them and you.” Just 10 days later, the jolly time included a menu of “oyster cocktail,” “chicken consomme en tasse,” “sweetbreads en casserolettes,” “filet mignon with champignons,” and something called “ice cream, piece de resistance” (see image 3). The party roared on into the night at the Terrace Garden on East 58th Street, at the time a popular venue for German-American events.

Image 3

“While we made the conscious decision to not serve tutti frutti ice cream logs as in the 40s, we will be offering a dessert table with an assortment of French pastries after dinner,” said Carolina Navarro, HSNY Deputy Director. “We hope to build on our gala success every year, so for 2023, we're reopening Harvard Hall for after-dinner drinks, live music and mingling. Perhaps we will bring back cigars one day?”

The photographs below (images 4 and 5) show a history of the organization that members produced in honor of the 50th anniversary in 1916; the cover includes our Latin motto, “Ut tensio, sic vis.” This is a version of Hooke’s law of physics (in English “as the extension, so the force”) which governs the expansion and compression of springs, including those used in watches. In image 5, resident jokester and comedy songwriter Rochus Salomon is pictured just above the words “executive committee.” It would have been a tight field in a mustache competition.

Image 4

Image 5

In 1918, the smoker program included a song in English, “Watchmaker’s Smiles,” written for the occasion by Salomon, a native New Yorker who had studied horology in Europe and later served as president of HSNY. “Watchmaker’s Smiles” refers to several current events in its lyrics: “It may be forever we part from the booze/ And it may be for only a while” speaks to the looming threat of prohibition. Conditions are already deteriorating: “We have heatless days/ We have meatless days/ In these piping days of war.” Inflation is happening, too: “The bills in your vest/ Look like tips at their best/ When the price of some things you tell.”

The song’s reference to World War I hints at one of the reasons it’s in English, not German. Germans had become a national enemy and the Society’s members needed to demonstrate American patriotism. It’s the same reason our 1916 banquet menu suddenly featured the lyrics to “The Star-Spangled Banner.” HSNY membership was also growing more diverse around this time, and not every member spoke German well enough to sing merry songs in Deutsch.

The 1918 song goes on to personify watches according to various political personalities, for instance, “One that will not tick/ is a ‘Bolshevik’.” It also decries “bracelet watches” (wrist watches, which were rapidly gaining in popularity) as “vile”: “You should sweep from the bench”/ This trash into a trench.” It then devolves into an increasingly chaotic chorus, ending in mockery of women’s successful campaign to gain the right to vote. Nevertheless, the diversity of topics covered in this short excerpt shows the kind of society HSNY was: working watchmakers who were concerned about tight budgets and politics as much as trends in horology.

HSNY’s biggest celebrations have been on milestone anniversaries: 50th, 75th, 100th and 150th. Throughout the century, as one 1938 program put it, among our “social and entertainment endeavors…our best efforts are concentrated on our annual banquet and ball…one of the most important trade entertainments of the winter season.” A 1937 group photo (image 6) shows a crowd of about 300 members and partners dressed in tuxedos and silk dresses, with the head table at left accommodating those in leadership positions.

Image 6

Image 7

1941, our 75th year, was also a particularly patriotic one, taking place just a few months before America entered World War II. An American flag adorns the cover of the program for the “dinner-dance,” and a portrait of George Washington is stamped on the inside (images 7 and 8). The menu hasn’t changed much since 1916 though: still a lot of celery, olives, chicken, and potatoes, with petit fours and a “tutti frutti ice cream logue” for dessert (image 9).

Image 8

Image 9

In 1966, on the occasion of our 100th anniversary gala, the mayor of New York City declared February 26 “Horological Society of New York Day.” After the 1960s, HSNY’s gala programs became simpler and shorter, so I don’t have as much information about what members were eating, but we do have some pictures from the 1960s that show they were snappy dressers, celebrating in style. Image 10 shows our 94th Anniversary Banquet on Valentine’s Day, 1960.

Image 10

Although we’ve updated our menu for 2023, we’ll continue HSNY’s century-plus-long traditions at this year’s gala at the Harvard Club on April 15.

“If you look closely at our gala pictures you can see something interesting," said Navarro. "No, not a picture of Nick Manousos back in 1921 as if he has always been the HSNY caretaker (The Shining reference, anyone?). If you look closely you will find the faces of the very watchmakers and supporters who built up the American watch industry and were dedicated to HSNY's mission we still live by today — to advance the art and science of horology.”

HSNY Welcomes Oris as a Sponsor

The Horological Society of New York (HSNY) announces Swiss watch brand Oris has joined as a sponsor.

Founded in Hölstein, Switzerland in 1904, Oris is one of a small handful of Swiss watch brands that makes only mechanical watches, constantly striving to make better watches that offer beautiful, innovative functions and advanced performance levels.

Through its Change For The Better program, Oris is committed to a more sustainable future by certifying their climate neutrality in 2021 and issuing a Sustainability Report in 2022. This includes collaborations with New York City’s Billion Oyster Project, Florida’s Coral Restoration Foundation, and sustainable Swiss deer leather company Cervo Volante.

“As a manufacturer of purely mechanical watches for over 119 years, the art of watchmaking is integral across every facet of our business,” said V.J. Geronimo, CEO – The Americas, Oris. “We’re thrilled to join the Horological Society of New York as a sponsor, in order to educate the current and next generation of watchmakers and enthusiasts. Oris is a brand rooted in the enthusiast community, and we are excited to support HSNY.”

HSNY welcomes Oris and thanks them for their incredible support!

# # #

ABOUT THE HOROLOGICAL SOCIETY OF NEW YORK

Founded in 1866, the Horological Society of New York (HSNY) is one of the oldest continuously operating horological associations in the world. Today, HSNY is a 501(c)(3) nonprofit organization dedicated to advancing the art and science of horology through education. Members are a diverse mix of watchmakers, clockmakers, executives, journalists, auctioneers, historians, salespeople and collectors, reflecting the rich nature of horology in New York City and around the world.

http://hs-ny.org

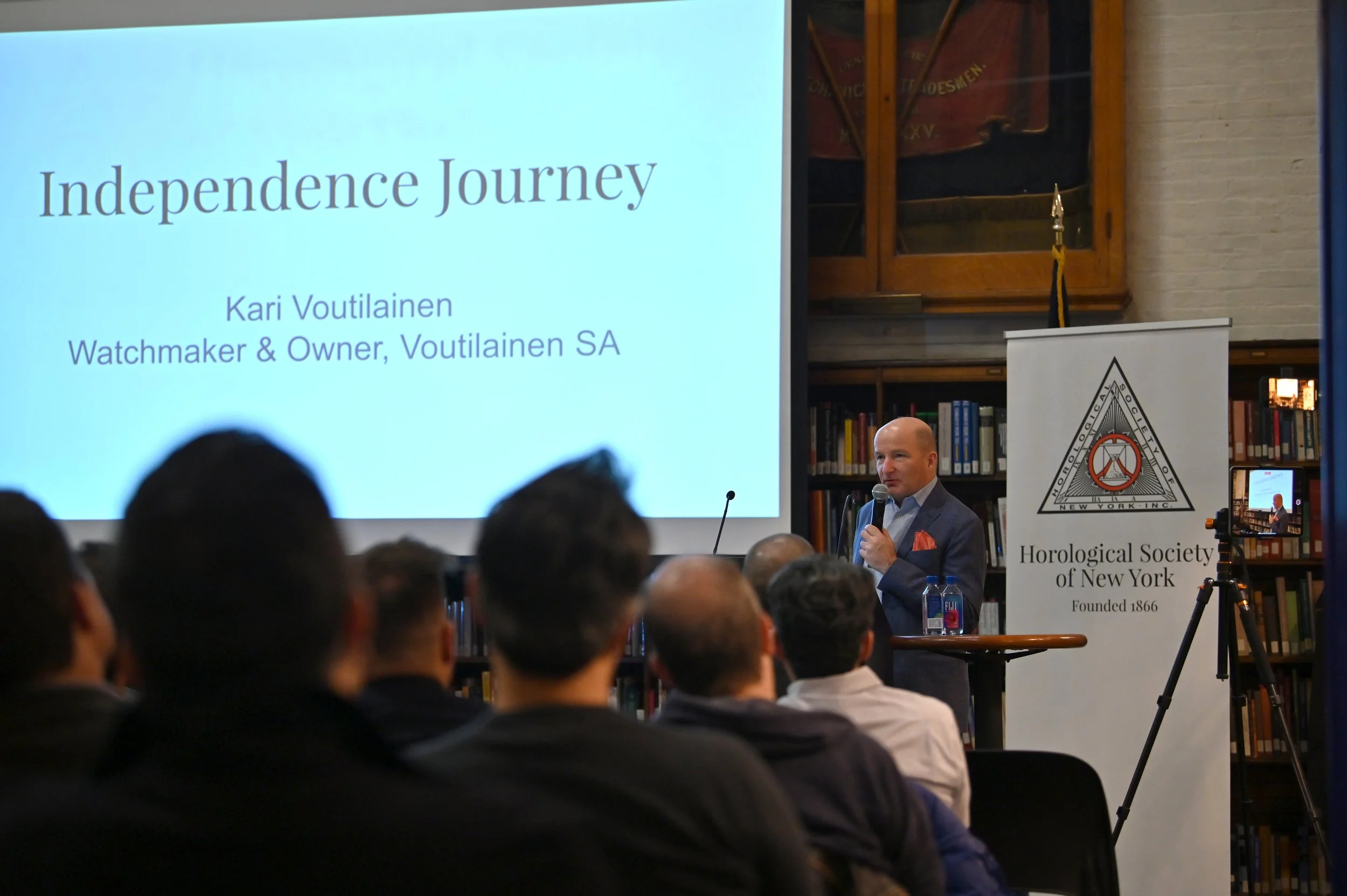

Previous Lecture: Independence Journey: From A One-Man Show To A Successful Independent

Kari Voutilainen, Founder and Owner of Voutilainen SA (Switzerland)

February 6, 2023

Video recordings of lectures are available immediately to HSNY members, and the general public with a two-month delay.

Photography by Bryan Bedder

Reading Time at HSNY: Four Centuries of Horological Books

This post is the fourth in a new series, Reading Time at HSNY, written by our librarian, Miranda Marraccini.

Image 1

The Horological Society of New York’s (HSNY) oldest books (see image 1) were published in the 17th century–a century in which Galileo and Shakespeare died, Newton discovered the law of gravity, and tulip mania raged in the Netherlands.

We have several books from this period housed behind glass in the rare books section of our Jost Bürgi Research Library in Midtown. In looking at the images below, you might be thinking, “those books don’t look 350 years old–they look better than some paperbacks I still have from the 70s.” There are a few reasons for this phenomenon, the main one being that during this period, and up until the early 19th century, European paper was made out of old linen rags rather than wood pulp. This early paper was very durable and less acidic than later wood-pulp paper, so earlier books generally tend to hold up better than later ones.

Image 2

Our earliest books are in Latin and French. One of our oldest (see image 2) is titled in the long 17th-century style: D. Petauii…Rationarium Temporum…In quo aetatum omnium sacra profanaque historia chronologicis probationibus munita summatim traditur. The very wordy title, which I’ve already shortened for ease of reading, includes the author’s name, Denis Pétau, rendered in Latin as D. Petauii. The rest of the title promises to tell over thirteen chapters “the sacred and profane history of all ages,” including “chronological proof” of when certain events occurred. Our copy was printed in Paris in 1652.

Surprisingly, given its length, the book is an abridged and summarized version of Pétau’s previous work. It attempts to put world historical events in order, a difficult task when taking into account different calendars in use in different eras and the relatively limited number of sources the author would have had access to. Pétau was a Jesuit theologian (and librarian!) whose work on chronology was highly influential, although he also wrote about the history of Christian doctrine and other historical and religious topics. You can browse a later version of this oft-translated text here.

Image 3

Tablettes Chronologiques (see image 3), published in Paris thirty years later, is also a work of chronology, covering the whole history of the church “in the East and the West,” including “the ecclesiastical authors” and “the schisms, heresies & opinions which have been condemned.” The title page tells us the book is a reference work “for those who read sacred history.” This book lays out history more schematically, as its title suggests (“tablettes” means “tables”). The text is arranged as tables and includes a shorthand system of symbols for different professions and identities, shown in image 3, on the left hand page. One symbol denotes a poet, while another indicates a mathematician.

Image 4

Another 17th century chronology in HSNY’s library, Les Elemens De L’Histoire (1696), has a bit more of a secular focus, including a long section about the history of noble families and their coats of arms, as well as the official symbols for royal government positions in different countries (see image 4.)

Although all of the books I’ve mentioned so far talk about time, none of them specifically addresses timekeeping or the tools that people invented to try to tell time. One book that starts to talk about horological instruments, published in 1691, is Traité D’Horlogiographie, a French treatise that discusses solar clocks and navigational devices. It has dozens of illustrations showing the most advanced scientific instruments of the time. We have a copy in our library, which is open to the public on weekdays.

Image 5

The gorgeous frontispiece (see image 5) depicts a castle flying a flag bearing the phrase “Rien sans vous” (“Nothing without you”), a motto that often refers to the influence of God and can be found in emblem books from this period. However, in this context one could also read it as indicating the importance of the celestial bodies, without which we wouldn’t be able to tell time or navigate. The scene around the castle shows the main subjects of the book: the stars, the sun, ships, a compass, navigational instruments, and geometric models. The image demonstrates how closely horology has always been tied to marine navigation and to astronomy.

Image 6

This book has two fold-out illustrations (see image 6) and about 70 other plates (see image 7) designed to help the reader learn the science of celestial navigation. Sundials are some of the oldest known timekeeping devices, and knowing how to read the time by the sun continued to be an important skill for navigators in the 17th century. The images demonstrate how the sun casts specific shadows when it’s at different angles to the horizon. Other diagrams in the volume show how to use the starry sky instead of the sun. In a future post, I’ll cover how 18th century inventors figured out how to accurately determine time at sea, which revolutionized navigation.

Image 7

Our copy of Traité D’Horlogiographie has a French inscription, probably from shortly after the book’s publication, that roughly reads “Make, O God, make me love you more than my possessions, more than myself” (see image 8). The book’s author was a monk, and it seems, given this prayer, that the owner of this copy too was a religious person, perhaps even a fellow member of a religious order.

Image 8

This book, however, is not wholly focused on Christian theological understandings of the universe. As you can see in images 9 and 10, the book includes the signs of the Western Zodiac, still recognizable today, and a palmistry diagram. As it is now, astrology was relatively popular during this period. Astrologers made predictions based on both in-person observations and diagrams in books. Our library contains a shelf of books on astrology, a record of the human quest to make sense of the vast, dazzling, and sometimes imperceptible sweep of existence.

Our 17th century books are small in number, but diverse in subject. Fortunat Mueller-Maerki, the previous owner of these books and HSNY’s librarian emeritus, defines horology very broadly. If you want to read about calendars, navigation, empire, philosophy, or religious ideas about time, we probably have something that will interest you. Time is what you make of it.

Image 9

Image 10

Welcoming New HSNY Members, January 2023

HSNY would like to welcome the following new members. It is only with our members' support that we are able to continue flourishing as America's oldest watchmaking guild and advancing the art and science of horology every day.

GOLD

Kevin Wong, Hong Kong

Luke Kowalski, CA

Philipp Krick, Switzerland

Phillip Tiongson, NY *

Prachi Gauriar, NY *

SILVER

Benjamin Groveman, NY

Derek Jang, GA

Maryhelen W. Jones, NM *

Peter Klein, FL

BRONZE

Aaron Schwartz, NY

Alexander Kapelman, CA

Andrew Nguyen, NY

Arthur Benning, PA

Ben Wilsker, NY

Drew Peterson, NY

Elliot Lum, NY

Erik P. Payn, PA

Ethan Goldwasser, NY

Garrett Kyle, NY

Hussein Roshdy, NY

John Bean, MI

John G. Sotir, MI

Jordan Lateiner, NJ

Joshua Peace, GA

Justin Rogers, NC

Kobi Benlevi, NY

Kyle Cooper, CA

Mario Marini, CT

Mark Roaquin, TX

Michael Paduano, NJ

Michel Ringuet, Canada

Myisha Cherry, CA

Rhett Lucke, NE

Ryan Bardsley, MA

Sergey Savin, NY

Siew Ben Leung, Cayman Islands

Stephen Bresett, NY

Steven Schwartz, CT

Terry A. Hamilton, TX

Zachary Rosenfeld, FL

* Upgraded Membership Level

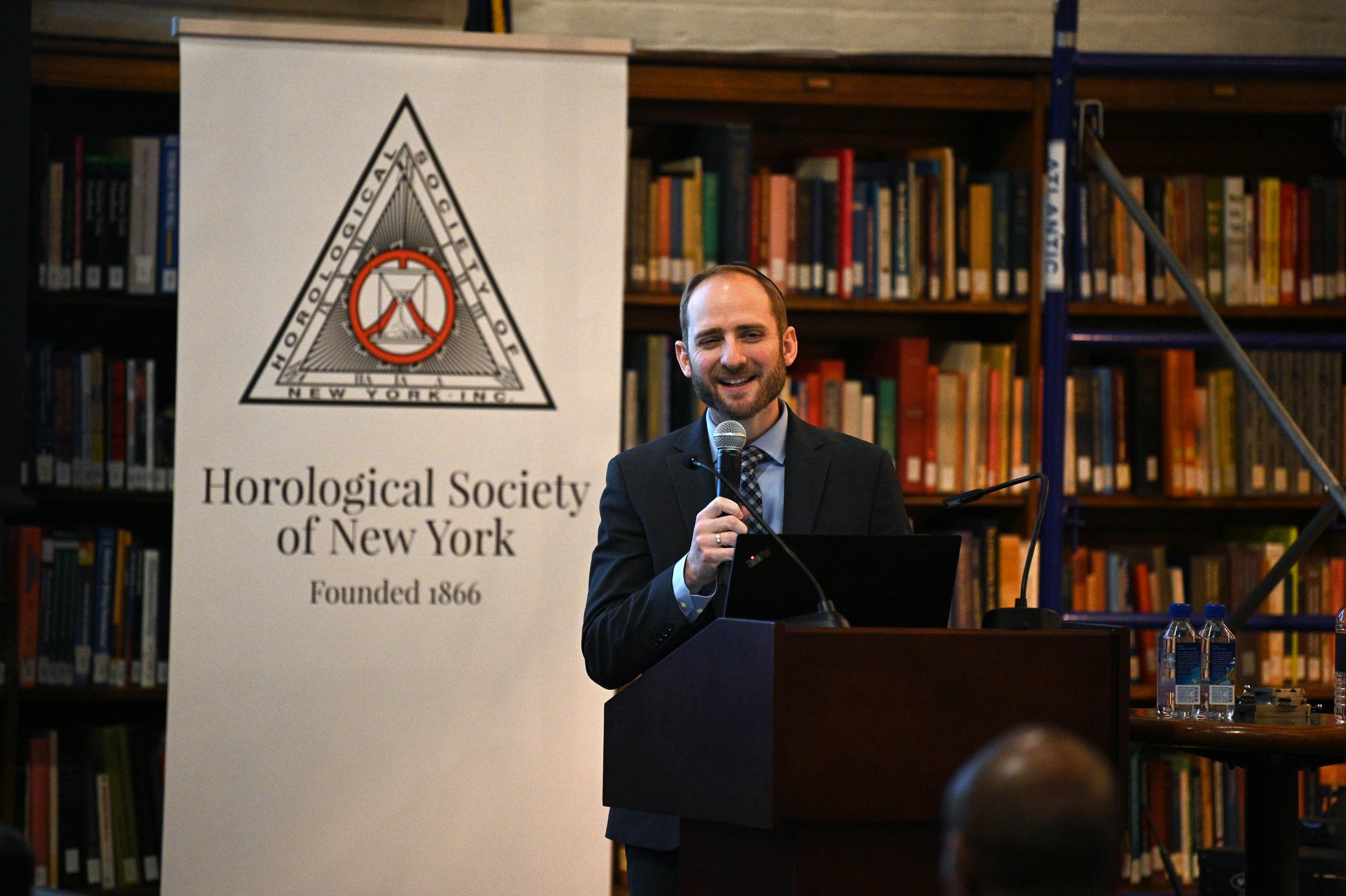

Upcoming Lecture: Independence Journey: From A One-Man Show To A Successful Independent

Kari Voutilainen, Founder and Owner of Voutilainen SA (Switzerland)

February 6, 2023

Watch manufacturing has always been a complex endeavor that requires expertise in many different areas. That expertise is usually spread out with a network of suppliers or a large manufacturer. Being able to concentrate that expertise with one small team, independent of traditional industry suppliers, is not an easy thing to do. But some watchmakers have done exactly this and have shown remarkable success. One such independent watchmaker is Kari Voutilainen.

At the February 6 meeting of the Horological Society of New York, Voutilainen will discuss his journey from a "one-man show" to a small and totally independent workshop producing incredible mechanical watches.

READ THE FULL STORY HERE!

Doors open at 6PM ET, lecture to begin at 7PM ET. RSVP is required.

The lecture video will be available to members immediately, and to the general public following a two-month delay.

Previous Lecture: The Birth, Death and Rebirth of American Watchmaking

Joshua Shapiro, CEO J.N. Shapiro Watches LLC (Los Angeles, California)

January 9, 2023

Video recordings of lectures are available immediately to HSNY members, and the general public with a two-month delay.

Photography by Bryan Bedder

Reading Time at HSNY: Hands of the Clock, Hands in the Book

This post is the third in a new series, Reading Time at HSNY, written by our librarian, Miranda Marraccini. Find the first post here and the second here.

Some might be tempted to think that all technology that exists today is digital, but as watch people, we know that watchmakers still use their hands–their digits–to create intricate, accurate, and beautiful timepieces. As a new member in the world of horology, I’m interested in this kind of artisan labor, and as a librarian, I’m also interested in a different kind of handiwork: handwriting in old books, that shows how these books were used and loved.

One example I recently found in the HSNY archives is a note in a book published in 1824 in London, The Book of English Trades.¹ This book, which was reprinted in many editions, would have been an important resource for young people seeking to learn how to get into “the business”–any business. It contains 78 trades listed in alphabetical order, with details of what qualifications you might need for an entry level position, and helpful illustrations that would allow someone who lived before the internet to understand, say, what a printing shop looked like, or what you needed to start making straw hats for a living.

In our copy, which can be found at HSNY’s Jost Bürgi Research Library, someone has written in an uneven nineteenth-century hand, “Augusta, Harriot & Edith Perry with their Grandmamma Booth’s Affectionate Love - - Bath 1st March 1855.” The inscription shows that multiple generations of women valued and used this book for at least 30 years after its publication, including a grandmother who thought it was important enough to pass it on to her granddaughters. And they thought it was important too–on the title page “Mrs Harriot Booth Widow” (probably the Grandmamma) signed it herself, and “edith” is written underneath in what looks like a child’s handwriting.

It is important to know that this book covers a number of trades in which women played important roles in the 18th and 19th centuries, including pin-making, spinning, and confectionery. These women may have been working in one of them, although I couldn’t find any definitive evidence of who they were or where they worked.

We own this volume because it contains an entry on watchmaking, “an employment so well known as to require no description” (nonetheless meriting a six page description). The entry, which includes the engraving at right, is lively and attempts to draw in young readers with anecdotes about famed clockmakers like Thomas Tompion, who “began the exemplification of his great knowledge in the equation of time, by regulating the wheels of a jack for roasting meat” (418).

But most of the text is practical, explaining how clocks and watches work, what a watchmaker does, and what the job requires: “a light hand,” “a strong sight,” as well as some understanding of “mechanics” and “mathematics” (421). It also foreshadows the increasing mechanization of the industry, which like most others, was experiencing rapid change during what would later be known as the industrial revolution: the “invention of engines for cutting the teeth” has “reduced the expense of workmanship and time to a mere trifle in comparison to what it was before” (420).

As for the book’s owners, Augusta, Harriot, and Edith, according to the text, they could participate in watchmaking as watch chain makers, a part of the trade that “appears difficult” but is actually “easy,” according to our author, and therefore suited to women (421). The Booth women, however, clearly educated themselves about the facts of many trades in which they were not especially invited to participate. They were proud of their ownership of this book and active participants in the dawn of the industrial era in Britain.

Despite a lack of encouragement to enter the trade, women were working in watchmaking, and we have evidence of that in our library too. A hundred years after the Perry women inscribed their book, watchmaking students Marinette Golay and Liliane Bandini were taking meticulous notes in their classes on “Horlogerie, Arithmétique, and Réglage” (watch adjusting). Today we have four of their notebooks in our library.

Below, images from Marinette Golay’s notebook show that she not only took great care in copying diagrams, she also seemed to relish the process of illustrating watch parts. Her drawings are both precise and beautiful, and they use color to distinguish the different parts of a watch, making it easier to follow how repairs could be made. In the image below right, Golay, studying the balance wheel and the hairspring, illustrates the right type of screw to use (domed) so as not to deform the rim of the balance wheel.

We also have three of Bandini’s notebooks, similarly in French, and dated 1953. In her notes below, she is equally meticulous in her drawings. In the first image, she takes notes on different types of hairsprings, noting the ratios required and what type of watch they would be suitable for. In the second set of pages, she observes an example of secondary error, following changes in amplitude and rate in a watch movement over five days.

I’ve chosen to photograph notebook pages with hand-drawn diagrams because they’re visually interesting, but many more of Bandini’s pages are filled with hard math, calculations about energy and force that any working watchmaker needs to understand at a basic level. Bandini and Golay weren’t just interested in the easy part. They went all the way down to the invisible equations that underpin all the work of the hands. And since we have some of their graded exam papers, we know they were pretty good at it.

What we don’t know about Golay and Bandini is what they did after watchmaking school–whether they actually worked on watches, either servicing them or in some other context. But in our library, we certainly have evidence of how other watchmakers worked. Around the same time that Golay and Bandini were studying in Europe, an anonymous watchmaker was writing and typing in a notebook, purchased at Woolworth’s, that is now also in our collection. In this ringed binder, the owner detailed their store inventory, took notes on different watchmakers and how to repair different models, and drew diagrams of watch parts.

The image at left above shows typed instructions for jeweling watches, or replacing the bearings of a watch, usually made from rubies, which allow the gears to rotate smoothly. The notebook’s owner has carefully illustrated different types of jewels and notes how to remove them when a watch needs repairing. At right there is a hand-drawn diagram of different types of staking punches, sets of tools used for multiple purposes in watchmaking, including to join or rivet different parts of the watch together. I don’t yet know who this watchmaker was, although the notebook and other details point to an American working in the 1940s and 1950s. Even without the owner’s identity, this notebook can still provide us with detailed information about how working mid-century watchmakers set up shop, and how they studied (and still study) different models to hone their craft and repair beloved watches for future generations.

As a longtime librarian who’s new to horology, I’ve already learned so much about watchmaking from this notebook and other materials in our collection. Many of our items–like this one–are unique, with only one copy in existence. People read them, wrote in them, and used them, often until they were falling apart. That’s what I find most valuable about working with this collection. It’s a privilege to preserve the words and traces of people who labored over centuries, contributing the work of their hands to the story of horology.

____________________________________________________________________________

¹ A different copy is available on Google books.

HSNY Welcomes Paul Boutros and Lenise Logan as Trustees

The Horological Society of New York (HSNY) welcomes Paul Boutros, Head of Watches, Americas, for the Phillips Auction House, and Lenise Logan, President of Kalpa Art Advisory, Inc., to its board of trustees. John Reardon and Brett Walsdorf fulfill their five-year term as a trustees, and Walsdorf assumes the role of Treasurer and Director of Special Events.

Paul Boutros

Paul Boutros is the Head of Watches, Americas, for the Phillips Auction House, helping to build the department since its launch in 2014. In October 2017, he led Phillips’ inaugural New York watch auction, Winning Icons, where Paul Newman’s Rolex “Paul Newman” Daytona sold for $17.8 million - the highest result ever for a vintage wristwatch sold at auction. A lifelong collector of wristwatches, Boutros is a specialist in their authentication and valuation. He serves on the Honorary Committee of the Gerald Genta Heritage Association and is an Academy Member of the Grand Prix d’Horologerie de Genève (GPHG). Boutros is passionate about educating others on watch collecting, having co-founded one of the first watch collecting clubs, the Watch Enthusiasts of New York, and previously serving as the Watch Columnist for Barron’s PENTA.

“As a longtime admirer of HSNY’s mission, it is a true honor to be elected as a trustee,” said Boutros. “I look forward to collaborating with fellow board members in assisting HSNY to further advance watchmaking culture, education, and scholarship in the United States.”

Lenise Logan

As an art advisor and exhibitions consultant for over 20 years, Lenise Logan is well-known in the art business and museum worlds. She has worked with some of the most successful auctioneer operations and logistics departments, at companies such as Christie’s, Sotheby’s, and Phillips. Logan has been responsible for some of the most valuable works of art in the world; to the tune of over three billion dollars. A founding member of Christie’s Corporate Responsibility Group, she continues this work by supporting companies worldwide in achieving their resiliency, diversity and inclusion goals. When it comes to collectors and artists, Logan has worked with the Dean Collection and Reginald M. Browne. Logan supports Black and Brown community-driven art collecting in these communities.

“With the number of watchmakers decreasing in America and less than 40% of watchmakers being African-American, Latinx, or Asian combined - there is work to be done,” said Logan. “As a newly appointed trustee of the Horological Society of New York, changing that disparity is paramount. Through exposure and scholarships, HSNY aims to break down systemic barriers and provide equal opportunities for all students pursuing watchmaking as a profession. Our ultimate goal is to create a just future for aspiring wristwear professionals by optimizing the currency we all share: Time.”

Horological Society of New York Board of Trustees, 2023

# # #

ABOUT THE HOROLOGICAL SOCIETY OF NEW YORK

Founded in 1866, the Horological Society of New York (HSNY) is one of the oldest continuously operating horological associations in the world. Today, HSNY is a 501(c)(3) nonprofit organization dedicated to advancing the art and science of horology through education. Members are a diverse mix of watchmakers, clockmakers, executives, journalists, auctioneers, historians, salespeople and collectors, reflecting the rich nature of horology in New York City and around the world.

http://hs-ny.org

HSNY Welcomes Europa Star as a Sponsor

The Horological Society of New York (HSNY) announces Swiss publishing house Europa Star has joined as a sponsor.

Europa Star, which is currently offered to HSNY members worldwide, operates a network of international publications covering the watch, jewelry and microtechnology sectors.

The company's origins date back to 1927, when Hugo Buchser, its founder, was a young Swiss entrepreneur with a passion for watches. An experienced traveler and globetrotter, he toured the world for his own watch brand called Transmarine and then had the idea to launch a guide for watch buyers as a first step into the world of publishing. This guide quickly became an essential tool for the entire watch industry.

Under the impetus of Gilbert Maillard, Buchser's son-in-law, who became president of the company in 1962, the network of magazines published in various continents and languages were grouped together under the Europa Star brand in order to cover all the international markets and become a truly global publishing company, establishing Europa Star as a leader in the watch industry's specialized press.

“As a publishing house that has been active for almost a century in promoting the art of watchmaking around the world, we naturally identify with the great educational work of the Horological Society of New York,” says Serge Maillard, director of Europa Star and great-grandson of the founder. “The way HSNY has reinvented itself over the past decade to speak to new generations of watch enthusiasts is truly remarkable and inspiring to us.”

Today, Europa Star is spearheaded by a fourth generation with Serge Maillard serving as publisher and CEO. Among the most memorable recent achievements is the digitization of the publishing house's archives, bringing the total content available online to over 250,000 pages covering almost a century of watchmaking history.

HSNY welcomes Europa Star and thanks them for their incredible support!

# # #

ABOUT THE HOROLOGICAL SOCIETY OF NEW YORK

Founded in 1866, the Horological Society of New York (HSNY) is one of the oldest continuously operating horological associations in the world. Today, HSNY is a 501(c)(3) nonprofit organization dedicated to advancing the art and science of horology through education. Members are a diverse mix of watchmakers, clockmakers, executives, journalists, auctioneers, historians, salespeople and collectors, reflecting the rich nature of horology in New York City and around the world.

HSNY Introduces Three New Financial Aid Opportunities for 2023

Honoring Innovation in Horology, Watchmaking Students & School Watches

The Horological Society of New York (HSNY) is welcoming 2023 with three brand new financial aid opportunities for watchmaking students in the United States: The Charles Sauter Scholarship for Innovation in Horology, the Charles London Scholarship for Watchmaking Students, and the Simon Willard Award for School Watches, created to further support HSNY’s mission of advancing the art and science of horology.

About the Charles Sauter Scholarship for Innovation in Horology

Horology may seem like a mature science, but there are still opportunities for improvement in all aspects of the field. There are many examples of innovations in horology that improved our lives, and HSNY is committed to fostering meaningful innovation through scholarship.

Charles Sauter

A Pennsylvania native, Charles Sauter (1922–2016) studied mechanical engineering at Pennsylvania State University and later studied watchmaking at the Hamilton Watchmaking School. After a stint in the U.S. Army, including time at the Manhattan Project, Sauter joined Bulova Watches as an instructor, where he encompassed many different positions including working as the Principal Engineer for the Accutron watch and as the Principal Engineer for the Apollo 17 Lunar Seismic Profiling Experiment.

A true innovator, Sauter has two patents to his name, for a micro-miniature stepping motor and an anti-backlash gear. In addition, Sauter was an active HSNY member, writing frequently for the Society’s newsletter, The Horologist's Loupe.

Today, HSNY is proud to create a scholarship opportunity to honor Charles Sauter’s innovative spirit and contributions to society, made possible by the generous donation from Amit Puri, CEO Kurtek LLC and Matthew Rosenheim, CEO of Tiny Jewel Box. Puri and Rosenheim share a passion for horology and a dedication to preserving the craft for future generations, and as supporters for decades, they are determined to preserve the wonders of horological science for generations to come.

“The micro-mechanical nature of fine watchmaking has always intrigued me, and for decades I have been fortunate enough to experience the amazing creations of great horological artists,” said Puri. “Now, by giving back to this field of study that has brought me so much joy, I hope to help facilitate access to learning the wonders of horological science for generations to come.”

“Establishing the Charles Sauter scholarship is a way for Tiny Jewel Box to both give back to an industry that has given much to my family, and help ensure the watch industry’s future success through supporting the education of more watchmakers,” adds Rosenheim.

About the Charles London Scholarship for Watchmaking Students

While most watchmaking schools in the U.S. are free, students often have to cover the expenses of watchmaking tools. These schools are full-time two-year programs, meaning paying for living expenses can be difficult. This is where the Charles London Scholarship for Watchmaking Students comes in.

Charles London

Charles London was a self-taught clock maker when he emigrated alone from Europe to Glen Cove, New York in 1923. London would go from house to house on the Gold Coast of Long Island selling his clock repair services to make enough money to send for his wife and three children to join him in the United States. In 1926, London established his own store selling and servicing clocks and watches on School Street in Glen Cove. With the changing fashions of the roaring twenties, he evolved his store to include jewelry and London Jewelers was born.

The entrepreneurial spirit of the New York horological industry in the early 20th century was exemplified by Charles London. HSNY hopes to encourage existing and future watchmakers to pursue their passion for horology with The Charles London Scholarship made possible by a generous donation from London Jewelers.

“London Jewelers and the Udell family are very pleased to have established the Charles London Scholarship for the next generation of skilled watchmakers,” said Mark Udell, CEO of London Jewelers. “Our goal is to inspire and encourage students to follow their passion of watchmaking to a career that supports the growing population of watch enthusiasts.”

About the Simon Willard Award for School Watches

Watchmaking schools often ask their students to create a school watch before graduation, allowing students to showcase the multitude of skills learned in watchmaking school. The finished product can be the first step towards independent watchmaking — an art that preserves traditional watchmaking techniques. Making school watches is important, and HSNY wants to help motivate watchmaking students to go the extra mile in their last school project.

Simon Willard

Simon Willard (1753–1848) was an important American horologist and trailblazer in the American horological industry. The Willard family clockmaking business was among the first in the U.S., setting up shop around 1780 on Roxbury Street in Boston (later known as Washington Street). Willard’s brother Aaron settled a quarter mile away, and from the 1790s onward, the Willard family workshop built tall clocks in great numbers and performed general clock repair. In 1802, Simon Willard obtained a patent for his famous eight-day "banjo" clock, which is widely considered to be one of the most significant styles of early 19th-century American timepieces.

Willard's clocks required skilled hand-craftsmanship, and their movements were outstandingly precise. His own skills were exceptional, and he was able to file cogwheels without leaving file-marks, producing mechanisms with a margin of error of just thirty seconds over the course of a month. By about 1810, both Simon and Aaron were producing clocks that were as good as those being produced in Europe.

The Simon Willard Award for School Watches is made possible by a generous donation from Samy Al Bahra, a collector of independent timepieces and a proponent of traditional watchmaking education.

“I am excited to contribute to the Horological Society of New York's educational mission and I hope the Simon Willard Award helps motivate more watchmaking students in America to take the plunge of sharing their work with the rest of the horological community,” said Al Bahra.

Application details

Any student who has been accepted or is currently studying at a full-time watchmaking school in the U.S. is eligible to apply for financial aid. Prospective students may also apply, with the understanding that the scholarships are contingent on their enrollment at a full-time watchmaking school. The scholarships are awarded every April, with awards of up to $5,000 (Sauter and London scholarships) and $10,000 (Willard award) available. Individual requirements can be found here. The application period is from January 1 to March 1 of every year.

Additional Scholarship Opportunities

# # #

ABOUT THE HOROLOGICAL SOCIETY OF NEW YORK

Founded in 1866, the Horological Society of New York (HSNY) is one of the oldest continuously operating horological associations in the world. Today, HSNY is a 501(c)(3) nonprofit organization dedicated to advancing the art and science of horology through education. Members are a diverse mix of watchmakers, clockmakers, executives, journalists, auctioneers, historians, salespeople and collectors, reflecting the rich nature of horology in New York City and around the world.

http://hs-ny.org

Welcoming New HSNY Members, December 2022

HSNY would like to welcome the following new members. It is only with our members' support that we are able to continue flourishing as America's oldest watchmaking guild and advancing the art and science of horology every day.

GOLD

Adam Klein, GA *

Dustin Tsitouris, OH *

Lukas Senkowski, NY

Philip Chua, Singapore

SILVER

Brad Tucker, GA *

Jeff Lee, NJ

Sean Mccarthy, NY

Tim Paine, NY

BRONZE

Adam Stubbs, NY

Aimee Gruber, KY

Andrew Cannon, Canada

Anthony Tran MD, MS, PA

Antonia Gurkovska, IL

Brian H. Nussbaum, NY

Catherine Donnelly, NY

Daniel Daly, NY

Daniel Orgel, RI

Dave Lo, CA

David L. Schaeffer, NY

David S. Katz, IN

David Saunders, NY

Diego Avelino, FL

Dr. John Westerdahl, CA

Emile Devaux Jr., NY

Eric Abshier, VA

Fahd Haddoumi, NJ

Gary Berson, NY

Giancarlo Rosselli, GA

Greg Deligiannis, NY

Jackson Moore, OR

James Jones, GA

Jarrod Clayton, NC

Jay Klapper, NJ

Jerome Ballarotto, NJ

Jim Bazzano, NJ

John Asencio, NJ

John Chirigos, MD

John L. Marcantonio, NY

Jonathan Vingiano, NY

Joseph Viana, NY

Joshua Rebel, TX

Juan Ramirez, NJ

Karim Anis, MA

Kurt C. Jensen, MN

Lance Valenzona, Canada

Lynell Washington, CA

Mario Konrad, NJ

Michael McManus, NY

Michael Ruff, MN

Morris Vivona, NJ

Murat Kocak, Canada

Nicholas Sereda, MA

Oliver D. Cromwell, NY

Raymond Cho, NJ

Raymond Ko, NY

Riley Smith, CA

Robert Atwell, FL

Ronald Birchall, IL

Roy A. Causey, WI

Sean Noah, AL

Seth Archer, NY

Seth Robinson, NV

Stephen Faust, PA

Terri Cooper, CA

Thomas Gruber, KY

Tim Okito, MD

Timothy Erin, PA

Timothy Walsh, NJ

Tommy DeMauro, PA

Veronika Hebbard, Canada

Wayne T. Branom III, Washington, D.C.

Wojciech Dec, NY

* Upgraded Membership Level