Reading Time at HSNY: Ex Libris

This post is part of a series, Reading Time at HSNY, written by our librarians. Today’s post was written by Miranda Marraccini.

Have you ever looked at a book in your collection and thought, “I need to make absolutely sure potential thieves know this book is mine”? Or maybe just, “This book could use a little pizzazz”? If the answer to both of these questions is no, well, then we don’t have much in common. But if you’ve ever considered how to inscribe your books in a manner befitting your sparkling personality, then you might have something in common with both the author of this article and the former owners of books in our library at the Horological Society of New York (HSNY).

Although HSNY’s current collection is largely the gift of one generous bibliophile, Fortunat Mueller-Maerki, he bought most of his books secondhand. Many contain marks of their previous owners. I’ve often appreciated how these names and inscriptions add meaning to the books they adorn, telling stories about how people have used and loved them over the years. Most of the book traces I’ve written about previously have been handwritten, but in this article, I’ll focus on bookplates, which are printed expressions of ownership pasted to the inside of a book. Because our Jost Bürgi Research Library collection specializes in the study of time and timekeepers, former book owners sometimes bought or commissioned bookplates that incorporated horological themes.

Image 1

Of the bookplates I’ve snapped photos of, the one in image 1 particularly caught my eye, and you can probably guess why. It includes a six-pointed star, a naked woman tastefully framed from the back, and a number of symbols of the book owner’s interests including, clockwise from top right: a watchmaker’s lathe; violin and sheet music; executioner’s tools; escape wheel; quill pen; magic tricks; Egyptian symbols; a classical column; some things I can’t identify that look like fireplace tools; and a black cat with witch’s broomstick. The middle of the bookplate features the mysterious sator square, a Latin palindrome that has served as a mystical and religious symbol for hundreds of years. At the top and bottom of the central star, the Greek letters alpha and omega denote the Christian God.

Who, you might ask, was the owner of this book, apparently a person of myriad interests? Henry V. A. Parsell, Jr. was a multitalented Reverend (later Bishop), “electrical genius,” and engineer from a wealthy new-money New York family. He wrote a book called “Gas Engine Construction" and “made an exhaustive study of evolution, astronomy, archaeology, and many different philosophies,” according to a newspaper article about him. “Many different philosophies” included a now-defunct Masonic order called the “Egyptian Rite of Memphis,” which may explain the ancient Egyptian symbols in the image.

Parsell commissioned Jay Chambers, a well-known graphic artist and illustrator of the time, to design this bookplate–he was one of the three partners at the Triptych Designers of New York, named in the signature at bottom right. This bookplate is remarkably detailed and personal, even compared to others in our collection. I feel I know a little bit about the adventurous Mr. Parsell and I would like to know more, because he seems like an eclectic character, to put it mildly. More than that, though, I think this bookplate encapsulates the joy of our library collection as a whole: eccentric, multifaceted, varied, and strange.

Image 2

As you might expect, quite a lot of bookplates in our library contain imagery that reflects either the container (a book) or the subject (time). I’ve written about one before, a bookplate belonging to the late historian Silvio Bedini (image 2). It shows a person absorbed in study behind a chaotic rubble of books, with the motto “Satis Temporis Non Est Nobis” or “For us, there is not enough time.” Visitors to the library often ask me if I’ve read all the books in the library (ha!) or, if not, to estimate what percentage of the collection I’ve read. Readers, there is never enough time.

Gerald S. Ruscoe has gone a bit more obvious with his bookplate, in which an hourglass sits on a pile of books covered with vines (image 3). The text on the top reads “Books Span the Ages…” and also shows a lamp of knowledge producing smoke. Putting on my “professional bookplate critic” hat, I will say the design is a little tame. This book is comfortable resting on the shelf behind the couch. This book might be afraid of taking the subway.

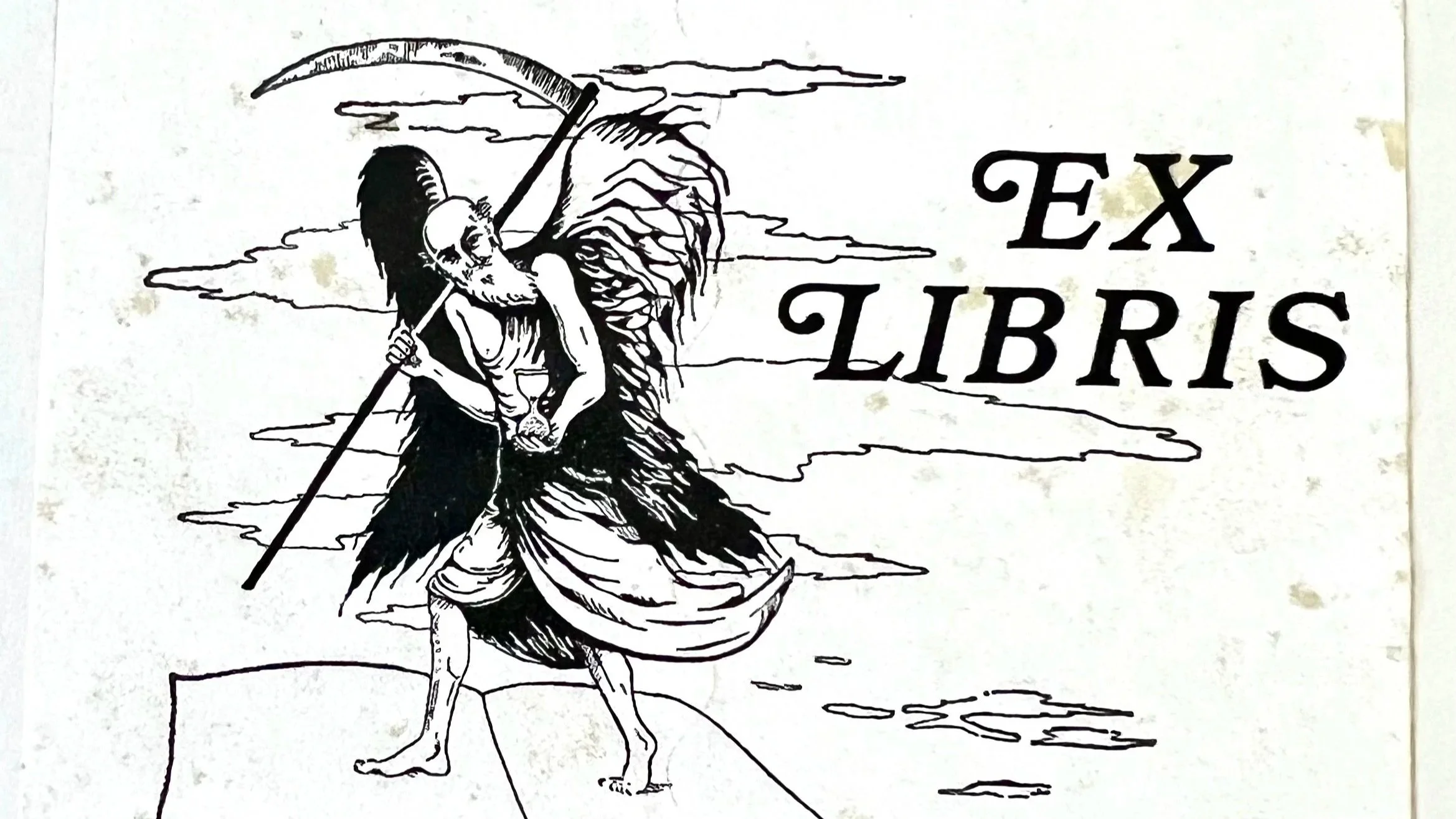

The same idea shows up in the bookplate of one F. L. Thirkell, although his imagery is more hardcore: Father Time shouldering a scythe, standing on the pages of a giant book that seems to be floating in the clouds like a sort of magic carpet of death (image 4). The bookplate says to me: your ride is here to take you away, and you won’t be coming back.

Image 3

Image 4

Thirkell was a Fellow of the British Horological Institute (BHI) who published in the BHI’s Horological Journal, including illustrated articles on how to repair specific models of watches. In my research, I didn’t find much about him as a person, but judging entirely from his bookplate, I would guess he enjoyed Black Sabbath (RIP Ozzy), gossiping with his pet rabbits, and scaring children with his Halloween decorations.

For the winner of the “most horological” award, I’d nominate the bookplate of Hugh L. Marsh, onetime treasurer of the National Association of Watch & Clock Collectors (NAWCC) (image 5). Marsh’s bookplate reproduces a hilariously over-the-top illustration from a late-17th-century book of fancy costumes.

Image 5

In the book, “Recueil les Costumes Grotesques et les Métiers,” each artisan wears the literal tools of their trade as clothes. For example, an apothecary walks around covered in bottles and funnels; a glass merchant dons mirrors and chandeliers. In this case, a watch-and-clockmaker wears, well, a ton of clocks. You can see the details better in the original image: he’s got chiming bells on his head, a coat festooned with dials and tools, and sleeves clank-clanking with watch cases at the elbows. It’s chaos. And, as two of my colleagues independently noted, it would make a great Halloween costume.

One of my favorites among the bookplates I discovered has absolutely nothing to do with time, books, or mortality. It’s a lovely Siamese cat, looking delightfully bemused to find itself inside “The Artistry of the English Watch.” As a cardigan-wearing librarian, I am, of course, a cat lover myself–I once acquired, in a white elephant gift exchange, a sign for my desk that reads “Ask me about my cats.”

Image 6

This cat bookplate belongs to Shelagh Berryman, one of the few female book owners represented in our collection (though many more are anonymous). A 1986 edition of The Music Box, an International Journal of Mechanical Music, reports that Berryman’s shop in the town of Wells contained the “second smallest museum in England”: “A large room above the shop…houses a collection of musical boxes of which browsers in the shop below who become entranced by the wonderful collection of goods on display for sale, may for a 50p fee, browse upstairs too. A demonstrator is present and these instruments are also for sale.” By 1988 Shelagh and her husband Douglas had expanded to a second shop in the bigger city of Bath, so they seem to have achieved a certain level of success.

Berryman owned at least two books in our collection, the other being “The Camerer Cuss Book of Antique Watches”. I like to think her bookplate expresses the multifaceted nature of many horologists, and in fact, most humans: sure, we’re watch people, but we can be cat people too. We have a sense of humor and whimsy about ourselves.

I’ll close with one last genre of bookplates I’ve noticed: messages to book borrowers. For example, the bookplate of George O. Keenan (image 7) contains a gentle warning: “I enjoy sharing my books as I do my friends, asking only that you treat them well and see them safely home.” Keenan, whom I couldn’t find much about online, clearly enjoyed lending volumes from his personal library to friends, as evidenced by the slip in this book. Evidently, he had no need to resort to a book curse to discourage thievery.

Image 7

Image 8

I’m not sure if anyone ever borrowed “United States Clock and Watch Patents,” but if you’d like to look at this very helpful reference work, you’re welcome to do so at our library anytime! And if you’re a member, you can even borrow it; just make sure to treat it well and see it safely home. Or if you prefer the more vulgar version, written in one of our other books owned by Cullen Tucker of Flemingsburg, Kentucky (image 8): “If this book should chance to stray kick it in the ear and send it home.”

For my part, I think my own fantasy bookplate design would feature some combination of my primary interests: tortoiseshell cats, fountain pens, watches, and of course, garlic (that last one might be a challenge to incorporate). What would your bookplate look like? Perhaps you already have one! If so, I salute you. I hope to see your bookplate proudly carrying your name into the far-off future, whether in our cozy library or as part of some distant collection, possibly in space, circling an unfamiliar star.